Something more or less like this has probably happened to all of us at some point: playing like wild things at 7 or 8 years old, ignoring the constant “you’re going to get hurt”, BAM! A blow to the head. In the background you can hear grandma saying: “Told you so. Careful, sweetie, neurons don’t regenerate!” (maybe grandma didn’t use exactly the words “neurons” and “regenerate”, the memory might be affected by the blow, but it’s inspired by real events). The truth is that neurons are the main type of cells that make up the brain, and for many years it was believed that, after a certain point, we have the neurons we have, and if we lose them, we never get them back: these are the ones there are, the one that’s lost, is lost, end of neuro-story. Well, no: today we know that it’s not quite like that.

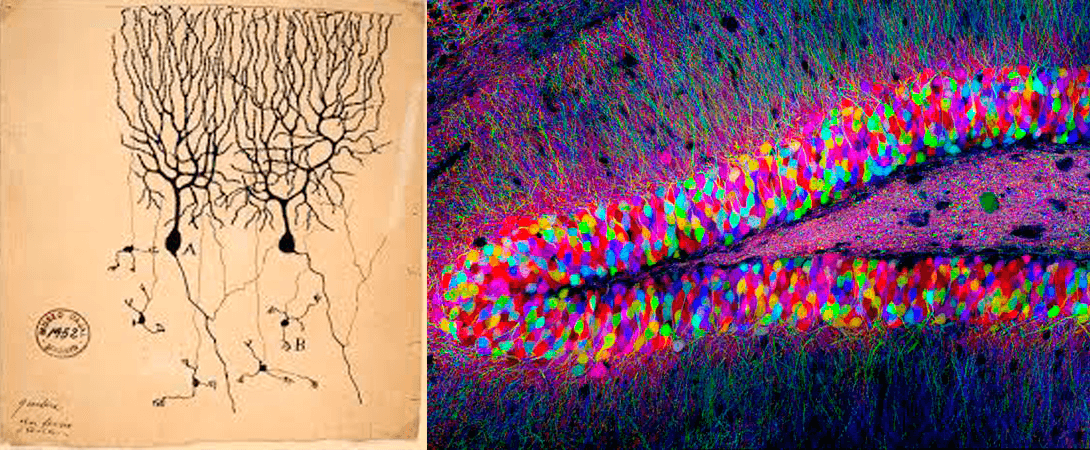

It all started more than 100 years ago with Santiago Ramón y Cajal (yes, it’s a single person, member of the Committee of Confusions along with Ortega y Gasset, López y Planes, Olaguer y Feliú, among others). Until that moment the brain was perceived as a single thing, a mass. What this Spanish doctor did was cut brain parts into tiny pieces and stain them with a solution that recognizes different cellular components, invented a few years earlier by the Italian Camilo Golgi (with whom he would eventually share a Nobel). Although the results he obtained weren’t crystal clear, his imagination took off and these stains allowed RyC to interpret what he was seeing; so much so that we owe him the first descriptions of the nervous system and his magnificent illustrations of neural networks.

Ramón y Cajal was the first to describe neurons; he proposed that they are separate and independent entities and that they don’t form a solid mass, but rather they touch and communicate with each other, passing on information through their projections. This was a topic of debate for many years, especially because no one really understood how they could be separate yet work so well as a whole.

During the rest of the last century, a lot of evidence was added to the debate: the brain’s ability to transfer electrical information, the discovery of particles that transmitted information (where the Argentine Eduardo de Robertis had a considerable influence) and a better general understanding of how a cell works. But it all started with the hand-drawn illustrations of Santiago Ramón y Cajal, the kickoff for a revolution that has lasted until today, when we can see each neuron in a different color from the rest.

Like a before-and-after but with colors. On the left, what Ramón y Cajal imagined, in his own hand and neuron. On the right, what we can see now with a microscope.

To obtain these drawings, he looked at adult brains (dead ones, of course), and one of the things he observed was that these cells didn’t multiply. Thus arose one of the greatest dogmas of neuroscience: once nervous tissue finishes developing and animals reach adulthood, neurons no longer reproduce. This claim was on somewhat shaky ground, mainly because even if you take cells that do divide under normal conditions, they wouldn’t do so in those cases, since the patients were dead (actually they could have, but under certain conditions). Things stayed there for almost a century. But the nice thing about ideas in science is that if available information increases and there is evidence pointing in the opposite direction, ideas can change.

To understand how something behaves, you need to be able to measure it (directly or indirectly). Seeing tiny things like a cell is not easy at all and it’s even harder to try to know what’s going on inside it. Sixty years ago a technique was developed that allowed scientists to understand which cells were dividing. When a cell replicates, it makes new DNA from what it already has and in the process it takes molecules from the medium in which it lives. So you can put in that medium a marked molecule, easy to identify; for example, one that is used in this DNA synthesis. This makes the daughters of a cell that has divided carry that mark (radioactive), making it much easier to measure how many and which cells came from the same mother.

Using this technique, a Hungarian researcher named Joseph Altman began to see these radioactive labels in cells from certain areas of the brains of adult rats, which indicated that they were dividing, something that went against what was believed at the time. The general scientific community didn’t pay much attention to him. You had to be very bold to dare say that Ramón y Cajal, a Nobel laureate, had been wrong. Luckily Altman was that bold, and in the ’80s, timidly but with increasing force, people began to talk about the process by which new neurons are generated in organisms that are already in adulthood: adult neurogenesis.

Once this idea picked up speed, reports started to arrive showing that this process also occurred in reptiles, birds, humans and in almost all mammals. In the latter it occurs only in two very small areas of the brain. The neurons originating in one of these areas, the lateral ventricles, end up migrating to the olfactory bulbs, where they are believed to have functions related to smell.

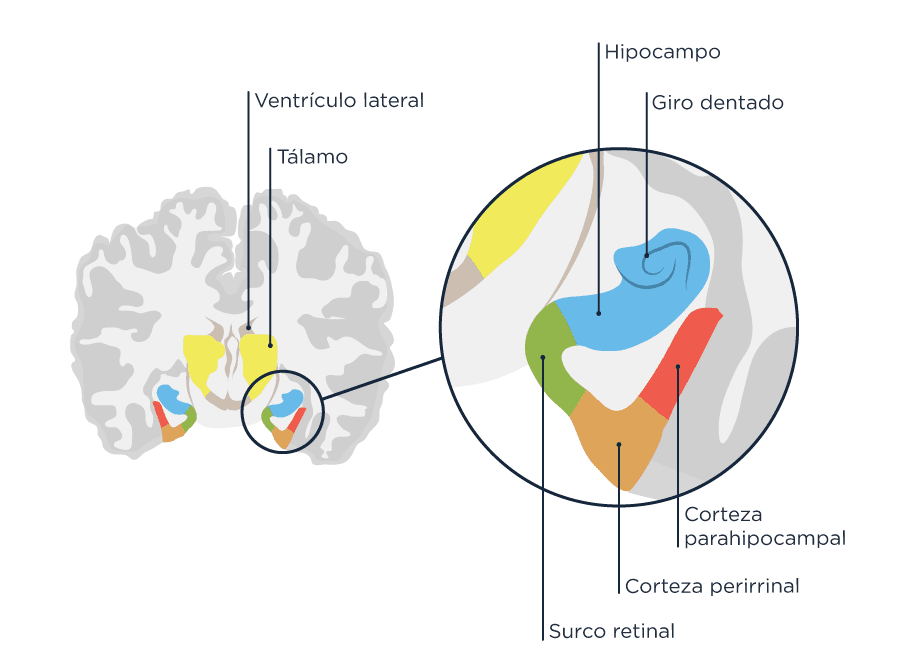

However, all eyes are on the other area, located in the lower part of the brain: the hippocampus, so called because, in primates, it has the shape of that romantic little sea creature.

In case someone asks what you’ve got in your head.

Inside this structure, which is quite complex internally, there is a small band of neurons that are positioned as if making a turn, forming a C: the dentate gyrus. Inside it there is a very thin layer of cells that are distributed along the edges, called the subgranular zone. It is only there, in the depths of the hippocampus, where neurogenesis occurs in adults. The process can be divided into several stages depending on who describes and writes about it, but in general there are 3: the cells divide (proliferation), acquire the characteristics of the specific neurons of that area (differentiation) and only those new ones that manage to make efficient connections with the old neurons survive (survival).

We are generating new neurons all the time. It is a process that occurs naturally and we’ve known about it for so little time that we still don’t understand what function it serves. Although, as happens in many vertebrates, the most likely thing is that it is associated with some important function, such as giving rise to certain types of neurons that are believed to be related to various hippocampal functions such as spatial memory and, most interestingly, emotions.

Although in different animals, such as rodents or birds, it is very well established that this process is important for brain functions, nowadays there is still controversy about whether it really occurs at significant levels in humans (the most hardcore readers can dive into this debate here and here). The main problem in answering this question has to do with how complicated it is to carry out studies in living humans, since it’s obviously frowned upon to use the same techniques that are used in other animals, such as the radioactive labeling technique. So the people who investigate this turn to donated brains from deceased individuals and try to use other molecular strategies to find the new neurons, such as antibodies that label proteins expressed specifically in newborn or young cells. The thing is that working with dead material, just as it happened to Ramón y Cajal, has its drawbacks: a low number of samples available, the state of preservation of the samples, the degradation of the proteins being sought as a consequence of poor preservation conditions, etc. While this continues to be investigated, the strongest current evidence shows that there is indeed neurogenesis in humans in considerable amounts.

More neurogenesis and less Prozac

One of the ways to study and understand neurogenesis (adult hippocampal, but we’ll just say neurogenesis because otherwise it’s very long) is by increasing or decreasing its normal values (also called basal or physiological) and seeing what happens. Because the interesting thing is that it is regulated by many factors: internal ones, such as the response to a disease; and external ones, such as environmental stimuli or drugs. For example, it is known that aging and stress decrease the division of neurons, leading to lower levels of neurogenesis. The same can happen with drugs of abuse such as opiates, alcohol and cocaine. On the other hand, factors such as environmental enrichment that is, improving physical and psychological well-being through environmental stimuli such as toys or playmates, learning or physical exercise increase levels of neurogenesis (yet another reason to put Netflix aside for a bit and move around a little more).

Based on this, a few years ago people began to study what was happening in the brain in response to various drugs that might act as modulatory factors of neurogenesis. Probing different drugs, it was discovered that antidepressants, particularly those in the group that includes Prozac, after about 3 weeks of treatment also increase neurogenesis. Ta-da! This was a before-and-after moment because it marked a possible connection between neurogenesis and depression.

Depression is an affective illness (related to emotions) that is highly prevalent worldwide, and although it has been studied quite a bit, it’s still not very clear how and why it arises. But even less clear is the mechanism of action of the various antidepressants (and a whole bunch of other drugs) that are used, or why there are people who are resistant to these treatments and do not manage to relieve their symptoms. In the past, depression was linked to a molecule specialized in communication between neurons, a neurotransmitter called serotonin. In the brain, this neurotransmitter is involved in processes such as regulation of the sleep cycle, inhibition of aggression and mood states. The issue is that in many depressed patients, blood levels of serotonin are very low. And since there is a group of antidepressants (the Prozac group) that increases the amount of serotonin molecules, its lack was associated with the disease.

But not everything is that simple, and not every correlation implies causation, especially because not all depressed patients show significant decreases in serotonin. When the brains of deceased people who had suffered from depression began to be studied, it was found that they had fewer new neurons compared with people without depression. New hypotheses indicate that neurogenesis would be an important mechanism through which the hippocampus could change its neuronal connections by adding new cells, allowing it to adapt in the best possible way to environmental challenges. So, a person with faulty neurogenesis would be less able to adapt, which could result in stress and depression.

The balance is tipping more and more in favor of this hypothesis about problems in information processing and responses, leaving behind the idea of a chemical imbalance of certain molecules, including serotonin. As the Swedish Nobel laureate scientist Arvid Carlsson said, “However, it must be acknowledged that the brain is not a chemical factory but a highly complicated survival machine.” Thus, those of us who study neurogenesis hope that if we manage to decipher the molecular mechanisms behind the relationship between this process and depression, we might find new treatments that are more effective and improve the quality of life of people affected by this disease.

This entire field of neurogenesis is very recent; little is known, much is hypothesized and a whole bunch of questions keep (coming to) our minds. It’s not even entirely clear that this path some scientists are taking and studying is the right one, but it seems essential to us to try to understand a process that is happening to all of us, all the time, and that might help us understand many diseases.

The brain is an incredible mystery and studying it is like going into a Pandora’s box where sometimes we have no idea what we’re going to find, which is why it’s difficult and at the same time amazing to investigate it. Meanwhile, even though grandma wasn’t quite right, we should listen to her because she’s always a little bit right, and you never know when life is going to come along and wipe out a couple of important neurons with a big blow.