“It was beginning to be obvious: MDMA could be anything for anyone.”

Pihkal: A Chemical Love Story, Alexander Shulgin

Ecstasy, ‘E’, ‘crystals’, ‘molly’, different names for the same substance, which many people hope to find in their little Saturday night pills, although not everyone is that lucky. Because every week, more than a million people around the world pop pills and get popped by them, taking part in a kind of chemical Russian roulette because they don’t know if their pill is from the corner shop, from a lab, or deadly. After all, how likely is it that a pill produced by private individuals, with no ethical requirements and completely outside the law, will be subjected to the strict quality controls needed to guarantee the honesty of the dealer on the corner? (Rhetoric that becomes even sadder when you know that pill contents can be easily determined by tests with chemical reagents like Marquis, Mecke, Mandelin, etc. and different types of chromatography and spectrometry, but none of these methods can be used in Argentina, because pill testing is illegal, even though it would be enormously useful for preventing tragedies).

In technical terms, from chemistry, the much-coveted molecule is 3,4-methylenedioxymethamphetamine or (in its pronounceable version) MDMA. Its first official appearance occurred in a patent made public on December 25, 1912 by the German pharma giant Merck. But no human experienced the effects of this substance until several decades later, when it was rediscovered as a therapeutic agent and recreational drug during the 1970s.

However, its use for recreational, medical and scientific purposes was banned in 1985, a policy that failed spectacularly to reduce its popularity and consumption, although it did manage to completely halt legitimate and valuable scientific research on its uses in psychiatry and psychotherapy. The ban also failed to change another very important fact: MDMA exists, and like any drug that exists and produces feelings of well‑being in most people, it will continue to be sought and used clandestinely, bought on the black market and consumed in ignorance and in potentially harmful settings.

Special effects

June 3, 1929 constitutes a truly onomastic chapter for those who follow the series on drugs. Not the one about Heisenberg but the story of the discovery of psychoactive substances. That day, the American chemist Gordon Alles tested 50 milligrams of intravenous amphetamine on himself and later attended an event, thus becoming the first human being to show up to a party “super amped.” Apparently, according to anecdotal reports, that night he was especially talkative. Maybe it’s a coincidence, maybe not, but from day one it seems amphetamines and parties got along well.

A year later, on July 16, 1930, Dr. Alles orally consumed 36 milligrams of methylenedioxyamphetamine (MDA) hydrochloride, and two hours later, after feeling no effect whatsoever, and surely in the name of science, he took another 90 milligrams, reaching a total dose of about 126 milligrams. Thus, once again, Gordon Alles became a legend, by being the first person in the world to try an artificial empathogen, that is, a substance created by humans capable of producing empathy. Unlike amphetamines, this type of substance is not characterized mainly by its stimulating effects nor by generating physical dependence, but by its ability to produce deep (though fleeting) feelings of love towards other people.

MDMA (ecstasy) is a very close relative of MDA and is consumed for its psychoactive effects, some of which it shares with amphetamines, while others are completely different. Among them we can find: a sense of great well‑being, euphoria, empathy and love toward others (and even toward oneself), stimulation and changes in perception (touch, smell, and sometimes vision and hearing). MDMA can also increase sexual desire but at the same time makes it extremely difficult to reach orgasm and, depending on the dose, makes it impossible to maintain an erection. As Dr. Alfredo Miroli instructed good old Fleco in one of the milestones of human–cartoon interaction, “…we also call it the embarrassment drug, because it really ramps up your desire, it increases your drive, but wipes out your potency, you want to and you’ve got nothing to do it with, Fleco.”

Fleco going through the process of discovering that cartoons are not exempt from the dangers of MDMA, which include (according to Dr. Miroli) convulsions, sudden death and impotence.

But it’s not all love and male impotence. MDMA also dilates the pupils and raises body temperature to potentially lethal levels in the presence of risk factors. Some of these aggravating factors are dancing all night in a hot, poorly ventilated environment, without adequate hydration and feeling a constant but false sense of well‑being that prevents any warning of physical discomfort the body might try to send. Unfortunately, this is currently the most common context for its use.

Other problems that may be associated with MDMA use include the famous bruxism or “jaw clenching,” increases in heart rate and blood pressure, decreased appetite, insomnia, dry mouth, blurred vision, confusion, palpitations and tremors. Transient episodes of anxiety and depression can appear after the use of MDMA at certain doses (over 100–150 mg and especially when used continuously over time), which could be slightly eased by eating foods rich in tryptophan, such as bananas, milk or chocolate, or why not a good banana shake made with chocolate milk and post‑weekend regret.

Although bad MDMA trips are infrequent, when the substance “hits” (the famous come‑up) it tends to do so suddenly (especially if it’s the first time you take it), causing strong anxiety that lasts a few minutes. It’s like being launched in a ballistic missile toward the land of love and well‑being. Everything will be fine when you land (if no organ bails on you along the way), but until then you’re still flying inside a missile.

Unlike amphetamines (like those Alles took in 1929), MDMA (like what Alles took in 1930) is not known to cause dependence or withdrawal syndrome. It is usually classified as a psychoactive drug but not as a psychedelic drug; instead, it’s considered an empathogen (as we said, an agent that produces empathy) or an entactogen (which allows inner contact), terms we owe to chemist David Nichols and which were chosen because they appropriately reflect its ability to generate feelings of love (that of MDMA, not of Nichols).

Won’t somebody please think of the children?

Although science can inform us about the risks associated with drug use and how to minimize them, their legal status is always the result of an arbitrary process, influenced both by cultural factors and by economic and political interests. Throughout history, the use of drugs such as tobacco or even coffee has been persecuted with extremely harsh penalties. Today we could say –cigarette and cortado in hand– that those persecutions were an aberration. But nothing says that today’s persecutions won’t be seen as just as, or even more, aberrant. The inconsistency of prohibitionism over time shouldn’t surprise us because clearly so far it has not been based on objective evidence.

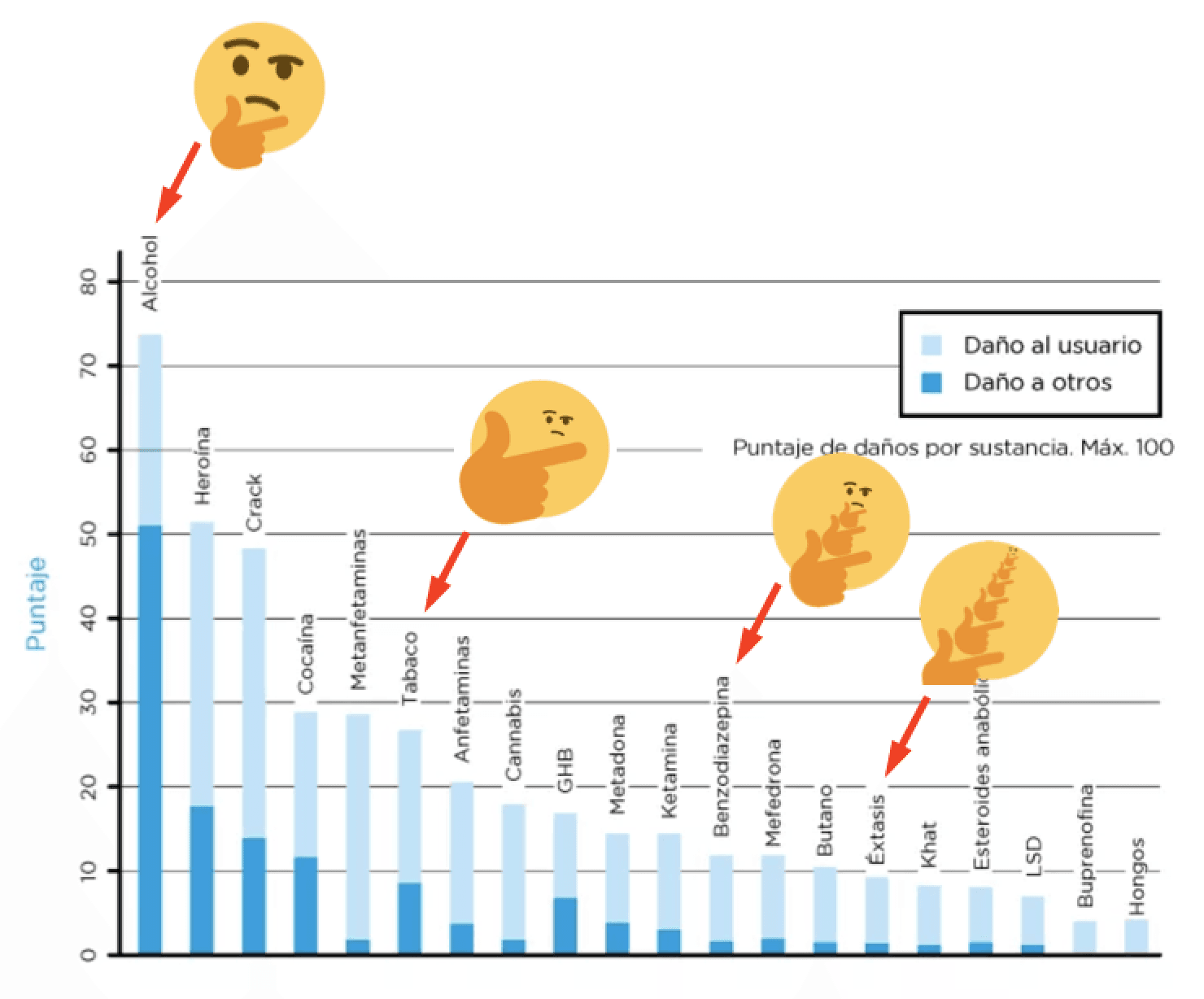

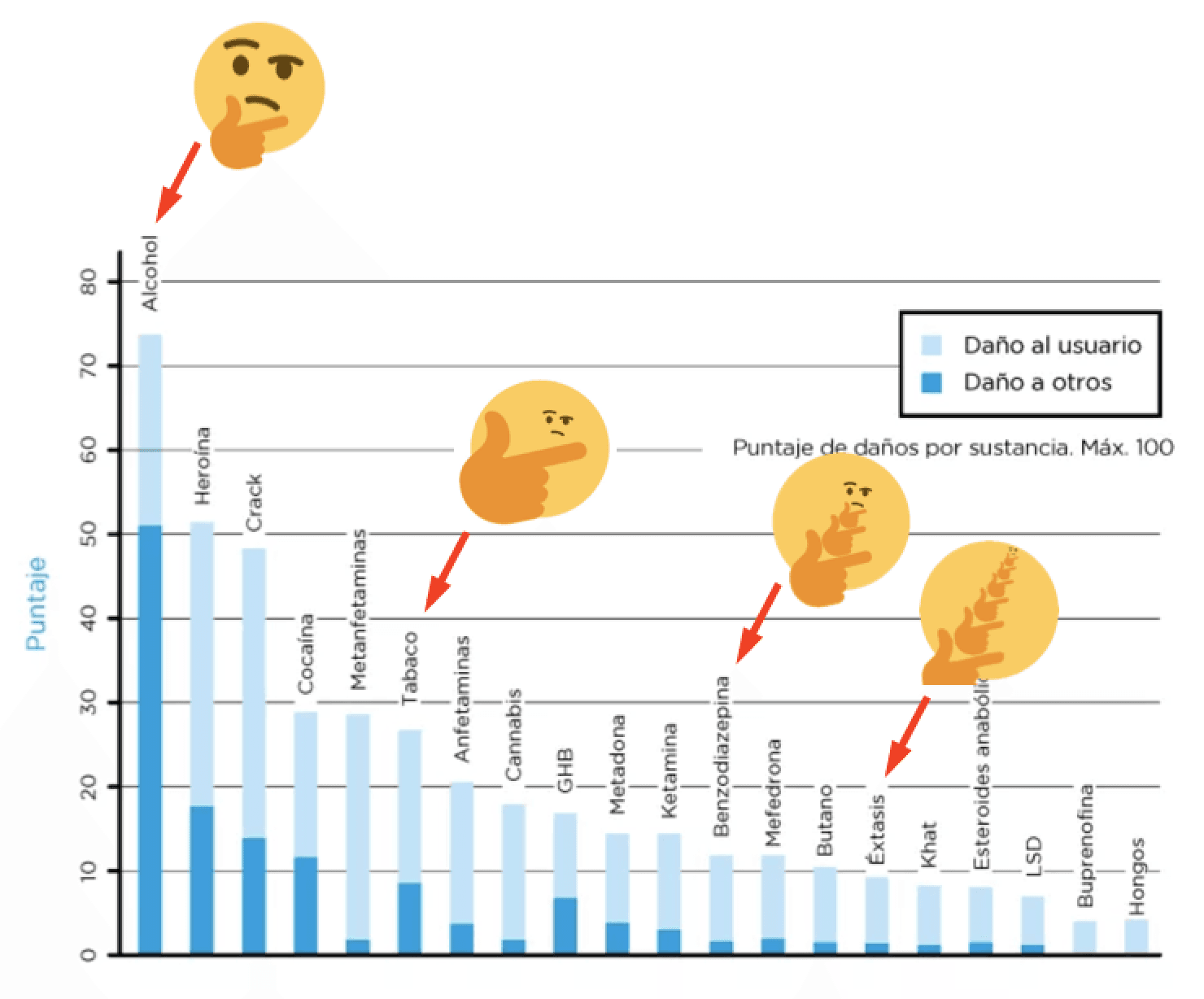

Our intuition yells in our ear that the criterion for the legality of a drug should be based on respecting the sovereignty of each individual over their own body, as long as its use does not harm others. The great English psychiatrist David Nutt and his team developed scales to measure harm to the user and to other people, and applied them to a variety of drugs frequently used today, both legal and illegal. The result will surprise you: in every sense, MDMA is safer than alcohol (the worst drug considering the sum of both types of harm), tobacco and benzodiazepines (which include familiar Rivotril or clonazepam, prescribed by many doctors to people whose health conditions do not warrant them).

Even though MDMA (‘ecstasy’) is a safer drug than others sold over the counter (alcohol, tobacco), possession can ruin lives in far more original ways, such as putting the user behind bars, or exposing them to unknown substances and doses, greatly increasing the risk. If it seems arbitrary and inconsistent, it’s because it is. Source.

Prohibitionism is exactly the opposite of what is needed to protect those who use drugs recreationally. For example, did you know that…

…alcohol can boost the effects of MDMA‑induced hyperthermia (increase in body temperature above normal)?

…alcohol dehydrates you?

…if you drink too much water to prevent hyperthermia, you can lose too much sodium (hyponatremia), with potentially lethal consequences?

…the most modern antidepressant drugs (known as serotonin reuptake inhibitors, Prozac’s mechanism of action, for example) tend to inhibit the empathogenic effects of MDMA? If a disappointed and unsuspecting user doesn’t feel its effects and increases the dose, they also increase the risk to their life.

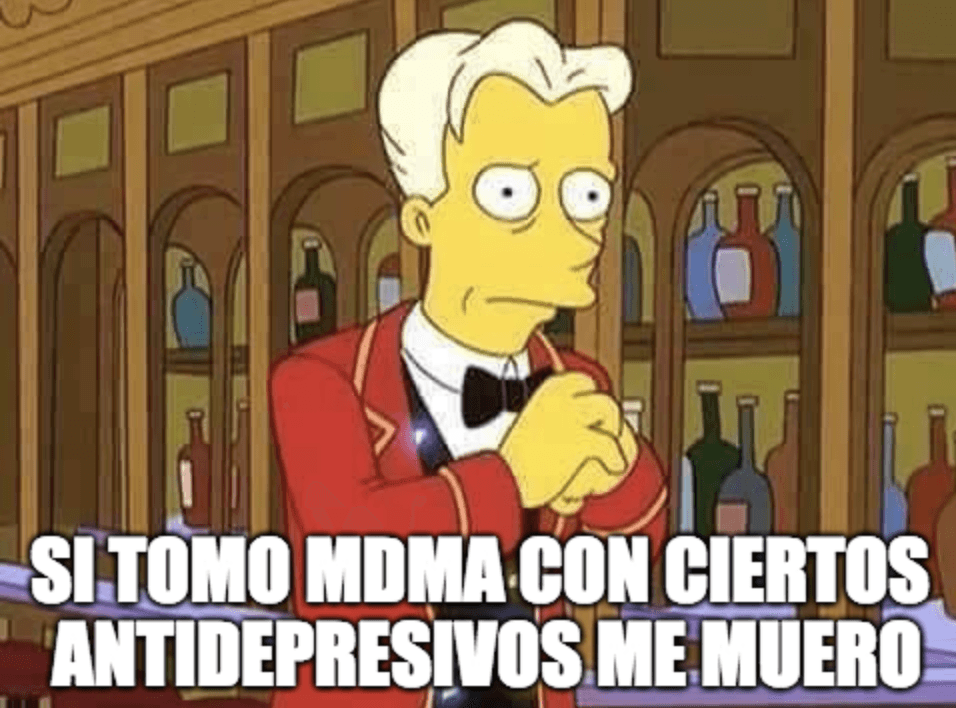

…MDMA combined with older‑generation antidepressants (known as monoamine oxidase inhibitors) can cause a dangerous syndrome known as “serotonin shock,” whose mortality is estimated at between 10% and 15% of cases?

…serotonin syndrome can also occur when combining MDMA with other very common prescription medications such as dextromethorphan (DXM), found in cough syrups, and the painkiller tramadol, commonly used to treat post‑surgery pain?

…the Amazonian brew ayahuasca can also produce serotonin shock when combined with MDMA?

…an ecstasy pill can contain other drugs such as amphetamines, PMA and PMMA, all with a much more problematic risk profile than MDMA?

If you didn’t know these things, don’t worry. It’s because nobody told us. And it’s because prohibition severely limits possible state interventions to reduce the risk associated with substance use. Where the state says “if you drink, don’t drive,” it cannot say “if you took MDMA, stay hydrated,” because in principle we’re not supposed to be taking MDMA in the first place. “Just say no to drugs” may be a great slogan for a TV campaign with 90s aesthetics, but it’s hardly going to help solve the problems associated with their use.

…and also if I mix it with DXM, tramadol, ayahuasca, and other drugs with similar mechanisms of action.

Where does this double standard come from? Why was Dr. Miroli on TV informing an imaginary being about the (wildly) dire effects of MDMA, while omitting that alcohol can also cause them, and in fact does so with greater severity and frequency? To answer these questions, it’s inevitable to dive into the history and peculiar chemistry of the substance. And what better way to begin than with sex… between lab animals.

A chemical love story: MDA and MDMA

Although we don’t know whether MDMA produces feelings of well‑being and love in rats, researchers at the University of Bari showed that the drug reduces interest in sex, as well as the ability to complete the act. But –and this is the key point– combining it with loud music significantly increases the animals’ promiscuity, while decreasing their probability of ejaculating even compared to ordinary levels, which as we know very well also happens in humans. The paper is titled “Effects on rat sexual behavior of acute MDMA (ecstasy) alone or in combination in loud music” and, among other things, it suggests why MDMA is so frequently used in the context of electronic music parties.

It’s unlikely that the scientists of the U.S. Army were aiming to cause orgies of sex and electronic music when in 1953 they classified MDMA as “EA 1475” and began a series of animal tests to investigate possible military applications (“EA” stands for “Edgewood Arsenal,” the famous inventory of psychotropic drugs investigated by the U.S. military). By not testing MDMA’s effects in humans (let alone on themselves), the military scientists failed to detect its empathogenic properties and classified MDMA as a drug of low interest. Although they probably wouldn’t have been very interested in bombing their enemies with MDMA to make them feel good and more empathetic and loving either. [The existence of the MKULTRA project –the research and use of psychedelic and hallucinogenic drugs for military purposes– has been documented since the publication of classified material in the 1970s. Martin A. Lee’s book “Acid Dreams: The Complete Social History of LSD: the CIA, the Sixties, and Beyond” contains a particularly gripping version of this story].

The first reports of MDMA use in humans date back to the 1970s. An improved synthesis of MDMA was published in 1976 by Alexander Shulgin (also known as “the godfather of MDMA”), and the first study of its effects in humans in 1978. The synthesis can be found in the book “PIHKAL: A Chemical Love Story,” written by Shulgin and his wife Ann. In PIHKAL, Shulgin explains in detail the reasoning that led him to synthesize MDMA from an essential oil. It starts from the observation that myristicin (an essential oil present in nutmeg) shows remarkable chemical similarity to MDMA. In addition, Shulgin knew that a sufficient amount of nutmeg can “hit” (although the trip is not very pleasant). Shulgin’s hypothesis of an in vivo (in the liver) transformation of myristicin into an active compound analogous to MDMA was never proven, but the organic synthesis inspired by this hypothesis is still popular.

Remember that the first person to experience empathogenic effects similar to those of MDMA was Gordon Alles, of whom it was said that he tried absolutely everything. The missing “M” in “MDA” tells us that its chemical structure is very similar to that of MDMA, except that the former is an amphetamine variation and the latter a methamphetamine variation. The effects of MDA are halfway between those of MDMA and truly psychedelic drugs such as LSD or psilocybin – a mix of empathy and universal love with sensory distortions, emotional volatility, disorganized thinking, altered sense of individuality and personal identity, and maybe a bit of panic and temporary madness. If MDMA is like a stroke of slightly psychedelic well‑being, MDA is more like a blow with a club: its effects last between six and eight hours (up to twice as long as MDMA), it can produce feelings of deep anxiety and its ability to irreversibly damage or even kill neurons is documented.

To understand how MDA and MDMA act in the brain, we must first understand the mechanism by which neurons communicate with each other. For most of them, communication is chemical, not electrical: one neuron releases a compound (a neurotransmitter) that binds to specific sites on the “wall” (membrane) of the other cell (neuron), triggering a reaction that contributes to its activation or inhibition. A more appropriate analogy for neuronal communication than an electrical network is that of a chain of dogs sniffing each other’s tails.

Once used, the neuron that released the neurotransmitter tries to recycle it, reabsorbing it through small pumps called “transporters.” Serotonin transporters find it easier to pull MDA or MDMA molecules into the neuron than serotonin itself. The result is that the neuron releases serotonin, but instead of recycling it, every time the transporter tries to bring a serotonin molecule back inside, it does so with an MDA or MDMA molecule. At the same time, it releases more serotonin, resulting in a net increase in the concentration of free serotonin “floating” between neurons, and a decrease in the concentration of MDA or MDMA.

More serotonin is associated with better mood and an increased subjective feeling of well‑being, although within certain limits. Serotonin also causes constriction of blood vessels, and its excess can lead to loss of blood supply, subsequent necrosis and the need to amputate some of the body’s twenty digits (men have a worrying total of twenty‑one limbs to lose for this reason). Psychiatrists prescribe drugs against depression that also bind to the serotonin transporter (a classic example is Prozac). By binding to the same site as MDA and MDMA, they take part in a molecular version of “Dancing for a receptor.” Because of this competition, this type of antidepressant tends to blunt the effect of MDA and MDMA. If a person diagnosed with depression doesn’t feel any lift from “ecstasy,” it’s very likely not because of their depression, but because of the medications they’re taking to treat it.

It is very important to note that both MDA and MDMA also act by increasing dopamine concentration, an effect they share with addictive drugs such as cocaine, sex or chocolate. The reason why neither MDA nor MDMA cause dependence is unclear, but it may have to do with the fact that they trigger a much larger serotonin release than dopamine release. Serotonin at least partially inhibits dopamine’s effect. But as the use of these drugs extends over time (becoming abuse), a drastic transformation begins to occur in the nature of their effects. And also in the brain, causing a complex series of irreversible changes whose net result is sadly obvious: the “magic” of MDMA is lost forever. The empathogenic effect begins to wane, leaving behind only the euphoria and stimulation typical of dopaminergic drugs. Pure wired‑up energy.

So we know the effects of MDMA and also how it works at the molecular level. But how do these molecular changes translate into the subjective sensations experienced under the influence of the drug? This is where much of current research is focused. Ultimately, the answer to this question requires research with humans, because lab animals are unable to communicate the sensations they experience. Functional neuroimaging studies show that MDMA reduces brain activity in the so‑called “limbic system,” where we find a set of structures involved in emotional responses, as well as regulation of anxiety and the so‑called “fight or flight reaction,” including the amygdala, hippocampus and hypothalamus. Moreover, these effects were stronger in subjects who reported stronger subjective experiences. Everything indicates that MDMA “switches off” the brain systems linked to fear and anxiety, which is especially useful for falling in love with anyone you meet, but remember that, sooner or later, they “switch back on.”

Mirror, mirror: who’s the trippiest amphetamine of them all?

Let’s imagine we see the world as it appears in a mirror: left and right are swapped, people have their heart on the other side of the body, and we talk about the magical right foot of Messi and Maradona. In this mirrored world, nothing is the same unless it is perfectly symmetrical with respect to left and right.

(Side questions: why do mirrors swap left and right, but not up and down? What’s so special about the horizontal plane that it’s affected by mirrors, while the vertical stays the way it is? Maybe we should write a whole piece about it, if only we knew the answer.)

Some molecules are perfectly symmetrical with respect to left and right, but neither MDA nor MDMA are. That means that when mirrored, they change, and we get other molecules called “mirror isomers.” The mirror isomers of MDA and MDMA don’t have more or fewer atoms than their original versions. The only change is that what used to be on the right is now on the left and vice versa, faithfully mimicking the trajectory of several political leaders.

Molecules such as MDA and MDMA exert their effects by docking onto other molecules that form part of the body. This docking can be ruined when we “mirror” a molecule. For example, imagine our hand is an MDMA molecule and a glove is the brain site where it binds to cause its effects. The wrong mirror isomer fails to dock, just as we can’t put our right hand in a left‑hand glove.

Isomers: graphical explanation (dramatization).

Molecules in the human body tend to favor one of the two mirror isomers. The chemical reactions carried out by drug traffickers to obtain MDMA produce a 50/50 mixture of both mirror isomers (half the molecules appear as the mirror image of the other half). Separating this mixture is extremely complicated, but it is possible to perform a chemical synthesis that yields MDMA molecules without a mixture of mirror isomers. In the late 1970s, Alexander Shulgin decided it was a good idea to gather his friends and start giving them increasing doses of the two mirror isomers of MDMA synthesized separately. One of them produced effects that could be described as “amped” (as we said, feelings of deep anxiety), while the other resulted in feelings of love and well‑being. Thus, Shulgin was the first to show that the “amped‑up‑ness” and loving‑kindness of MDMA are two sides of the same coin, or rather, of the same mirror.

Finally, it is known that one of the mirror isomers of MDA acts through the same principle as MDMA. However, when we mirror the molecule we obtain psychedelic effects comparable to those of LSD. That’s why people often say MDA (in a 50/50 mix of both mirror isomers) is halfway between MDMA and LSD. Two drugs for the price of one. What could possibly go wrong? Everything.

What is this? Can I ban it?

The spread of MDMA began among psychiatrists and psychotherapists fascinated by its ability to “unlock” difficult cases, especially those associated with severe trauma (post‑traumatic stress disorder, or PTSD, for its acronym in English). Its use began to be popular after MDA was banned in the early 1970s. The effects of MDMA seem almost designed for this purpose. The biggest obstacles faced by patients with PTSD are the inability to relive their trauma and talk about it without experiencing great anxiety, as well as the inability to entrust these traumas to a professional with whom they do not have a long‑term personal relationship. The state of well‑being caused by MDMA represents a temporary “shield” that allows one to revisit the most painful memories, while empathy makes it easier to open up during therapy sessions. Ann Shulgin, Sasha’s wife, estimates that in the early 1980s about four thousand therapists were introduced to MDMA, resulting in a similar number of therapy sessions accompanied by its use. Most of these doses were synthesized by Darrell Lemaire, a chemist and mining engineer who built an underground lab inside a volcanic crater. A real eruption of love.

Despite deliberate efforts to maintain a low profile, it didn’t take long for the usual psychonauts (we imagine most of them did not suffer from post‑traumatic stress) to notice that MDMA could be used without therapeutic aims, simply and plainly with the purpose of having a very good time. Recreational MDMA use exploded in the early 1980s, to the point that a group of entrepreneurs in Texas began selling it in neat little brown bottles under the name “Sasyffras” (derived from the name of the plant whose oil is used as the starting point for MDMA synthesis, sassafras).

People taking psychoactive molecules and dancing to electronic music? Entrepreneurs selling bottles filled with drugs? Strangers touching each other and having sex at parties? People having fun without consuming ridiculous amounts of alcohol!? This story repeats itself so often that it’s easy to guess the ending. In July 1984, the U.S. Drug Enforcement Agency (DEA) expressed its intention to classify MDMA as a Schedule 1 drug. This category not only includes drugs whose recreational use is illegal, but also those with “high potential for abuse” and “no recognized scientific or medical uses.” It fell to the DEA to prove that MDMA had these characteristics. But –for the first and only time in history– in 1985 the DEA decided not to wait to gather the evidence and declared MDMA a Schedule 1 drug on an “emergency” basis (its psychedelic cousin, MDA, had already entered this category in 1970). A drug less harmful than alcohol, tobacco and Rivotril, whose first users were members of the medical community, who researched it as a promising adjunct in psychotherapy sessions.

The World Health Organization responded by requesting guarantees for future scientific and medical research with MDMA. Despite the negative vote of this organization, MDMA was internationally classified as a Schedule 1 drug in February 1986. In a series of hearings convened by the DEA, two clearly defined sides faced off. On one side, the therapeutic community and patients who explored MDMA’s medical potential with remarkably successful results. On the other, a group of researchers announcing that MDMA produced brain damage, relying on studies showing neurotoxicity in animals after large injections of MDA (not MDMA). Humans never take MDA in such quantities and take it orally, almost never by injection. Moreover, brain tissue damage attributable to MDMA use has never been directly observed in humans. And finally, MDA is quite different from MDMA, as we already mentioned, regarding the activity of its two mirror isomers. It turns out that post‑truth isn’t as new as we thought.

As expected, the ban failed to put an end to MDMA use. Currently, hundreds of millions of doses are consumed per year, often manufactured in clandestine labs in Eastern Europe, sometimes belonging to bankrupt pharmaceutical companies. In Argentina, information provided by SEDRONAR indicates that 0.3% of the population between 12 and 65 years old used ecstasy (during 2017). On the other hand, it is estimated that up to 7% of the U.S. population has used MDMA at least once in their lifetime. The availability of MDMA on the European black market fluctuates and is of a magnitude comparable to that of methamphetamines. At times, MDMA trafficking expanded to involve Russian and Israeli mafias using ultra‑Orthodox Hasidic Jews as mules. Just to give you an idea of the scale of the whole thing.

The problem is that, when chemical precursors of MDMA are scarce, synthesis routes are followed that lead to products similar from a chemical point of view but associated with completely different effects and risks. One of them, PMA (known as an ingredient of Europe’s infamous “Superman” pills), was responsible for several deaths due to hyperthermia. The cure is worse than the disease, if only it were true that the ban counts as a “cure” and MDMA as the “disease.”

Was the DEA finally able to prove that MDMA meets the requirements to be classified as Schedule 1? Absolutely not, because there is substantial evidence that it doesn’t. The phrase “potential for abuse” is somewhat ambiguous, but it’s hard to imagine a definition according to which MDMA has such potential and ethyl alcohol does not. The problem is that there also wasn’t solid evidence of MDMA’s therapeutic potential. It turns out that the pioneers of its use had not followed a long and extremely costly, but necessary, procedure to guarantee the medical use of a drug: double‑blind, placebo‑controlled clinical trials. But one man was not in the DEA’s plans and, thanks to that man and his organization, clinical trials are now nearing completion.

Prescription ecstasy

It seems MDMA had therapeutic properties after all. Since the ban, Rick Doblin and his organization (MAPS, Multidisciplinary Association for Psychedelic Studies) have demonstrated, through a series of clinical trials adhering to the strictest standards, that MDMA has the potential to facilitate the course and improve the outcome of psychotherapy sessions for the treatment of different disorders. The trial for PTSD treatment is now in its final phase (phase III) and, if evidence supporting its efficacy and safety is obtained, the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) will be forced to approve its therapeutic use, which would imply leaving Schedule 1.

Locally, this does not, of course, mean MDMA will be sold with an ordinary prescription in any pharmacy. As with drugs with higher abuse potential (opiates and certain dopaminergic stimulants), MDMA will likely be sold through special prescriptions, and will be available only to a select group of health professionals. And although this change may not be relevant for those who use the drug recreationally, it will undoubtedly be vital for those who really need it: patients seeking treatment.

MDMA can be dangerous under certain circumstances, like almost any medication you buy today at a pharmacy. A drug’s package insert warns about its possible dangers and how to avoid them. If MDMA were approved as a medication, what would its insert say? Would “a feeling of immense well‑being and love toward all human beings” be listed among the side effects? It is important to understand that –as with any drug, legal or illegal– there are risks and potential harms associated with MDMA use. Ideally, the insert would have to cover each and every one of these possible risks.

Unlike legal drugs, whose use and potential adverse effects are continuously monitored, MDMA’s classification as Schedule 1 implies great ignorance of the risks associated with its use. Since we don’t know the global number of MDMA users, nor the circumstances of its use, it’s impossible to know what is happening. What we do know is that the incidence of adverse effects must be very low, because hospitals are not flooded with critical MDMA intoxication cases every weekend. It is estimated that mortality associated with MDMA is between 1 in 650,000 and 1 in 3,000,000 uses, numbers lower than those associated with many legal drugs of abuse and prescription drugs (15 times lower than paracetamol, for example).

Possible long‑term adverse effects are more difficult to determine. There are associations with disorders such as depression and anxiety, but the cause‑and‑effect relationship is not at all obvious: since MDMA results in a transient but intense sensation of well‑being, it is possible that people with pre‑existing depressive and generalized anxiety disorders decide to “self‑medicate” with this drug. There have also been reports of symptoms of various mental illnesses –psychosis, depersonalization (experiencing one’s own thoughts and personal identity as alien, distant), derealization (the feeling that the world is “unreal”), panic attacks, dissociation and paranoia– associated with MDMA use. The problem is that, in any population, a percentage of people will develop different psychiatric illnesses, and the population of MDMA users is no exception. When a drug is associated with highly heterogeneous disorders and the likelihood of developing them is independent of the dose or frequency of drug use, then the most parsimonious explanation is that there is no association between consumption and the development of the illness. In other words, someone can develop a psychiatric illness and at the same time use MDMA. And given the human need for simple answers to complex problems, we can expect a tendency to blame the illness on MDMA use.

Similarly, the long‑term association between MDMA and cognitive and memory deficits does not automatically imply a causal relationship. Long‑term use of other drugs (for example, cannabis and alcohol) can bias the results. According to psychiatrist Karl Jansen, several publications about links between MDMA use and mild cognitive disorders are inconclusive, since they do not include urine sample analyses and therefore cannot estimate the degree of polydrug use.

A more worrying aspect associated with MDMA use is its possible neurotoxicity, that is, its capacity to damage brain cells. Animal studies suggest that high doses of MDMA can cause neuronal damage, but it is very important to note that these doses are generally higher than those used recreationally by humans, and certainly higher than therapeutic doses of the drug (excessive, continuous MDMA use is also no guarantee of adverse effects. Jansen reports the case of a person who used 250 mg of MDMA intravenously EVERY DAY for six months, without experiencing psychiatric problems).

Even so, there is evidence that the brain of chronic MDMA users is “different”. For example, lower density of serotonin transporters, increased volume of fluid in the brain, and changes in electrical activity (measured with electroencephalogram) have been observed. The problem is that we don’t know the implications of these changes, even in the case of lab animals receiving exaggeratedly high doses of MDMA. Because despite having neuronal damage, their behavior is indistinguishable from that of perfectly healthy animals. In humans, although subtle cognitive deficits have been reported in chronic MDMA users, it is impossible to establish a causal relationship through retrospective studies, or to rule out the influence of polydrug use or users’ socioeconomic status.

In short: we have no idea about the long‑term damage associated with chronic MDMA use, because its classification as a Schedule 1 drug explicitly prohibits research on this drug in humans. It is possible that continued MDMA use results in neuronal damage of uncertain consequences. It is also possible that mood disorders are triggered after prolonged use over time. The important thing is that if we understand MDMA as a medicine, then its approval should not be blocked if its therapeutic effectiveness is demonstrated, given that there are conditions under which its use is extremely safe (which, incidentally, coincide with therapeutic conditions). And, like any medicine, we shouldn’t be surprised if its prolonged abuse in risky situations brings negative consequences. If someone grabs any medication off the pharmacy shelf and starts taking ever higher doses every weekend, it’s hardly surprising if their health deteriorates as a result.

Epilogue: cacti at war

One of Alexander Shulgin’s last published works is titled: “Ecstasy analogues found in cacti.” As the title indicates, it’s about molecules very similar to MDMA found in two species of cactus: Lophophora williamsii (‘peyote’) and Trichocereus Pachanoi (‘San Pedro’).

Many drugs of abuse are extracted directly from plant sources. Others are synthetic, but there are natural molecules with very similar effects, as in the case of LSD (a synthetic drug) and psilocybin (the active principle of various mushrooms of the genus Psilocybe). A common question is whether there are natural drugs whose effects are very similar or identical to those of MDMA. The usual answer is no, but Shulgin’s work shows that San Pedro (native to the Andes and common in northern Argentina) contains the molecule N,N‑dimethyl‑methylenedioxyphenethylamine, also called “lobivine.” MDMA has exactly the same atoms as lobivine (they are isomers), with just three of them in a different position.

How can we determine whether lobivine has effects similar to MDMA? By trying it, of course. Shulgin and company tell us there are “hints” of activity at doses approaching 50 mg, but apparently they did not continue increasing the dose. This is extremely unusual given Shulgin’s modus operandi, which essentially consisted of increasing the dose until establishing the drug’s inactivity or blowing his wig off (whichever came first). Given the history of MDA and MDMA, it is possible to speculate that the old adventurer was reluctant to raise the alarm, alerting both the authorities and the usual misfits to the presence of a “natural ecstasy” in San Pedro. So, just in case, don’t spread the word.

Because one of the clearest signs of the senselessness of the collective delirium called the “war on drugs” is the de facto ban on various plants and mushrooms, justified by the fact that they contain compounds declared illegal. The psychoactive molecules that governments around the world spend fortunes combating grow inexorably around us, in countless variations, many of which defy the imagination of chemists and pharmacologists. Banning them is as absurd as trying to ban earthquakes. However much we might want to govern nature by laws and decrees, nature is unlikely to cooperate.

The future regarding the therapeutic potential of MDMA and other synthetic and natural substances currently banned is more than promising. Let’s hope that, as a society in general and from the authorities in particular, this goes hand in hand with finally understanding that the prohibitionist framework has never shown positive results, but quite the opposite, and that, as in so many other areas, we begin to use current and potential scientific knowledge to improve people’s lives.

Note: as always, you can find more information on the history of the discovery, effects and risks of MDMA and many other substances at sobredrogas.com.ar