Two young fish are swimming along together and happen to meet an older fish coming the other way. The old fish nods at them and says: “Morning, boys, how’s the water?”. The two young fish swim on for a bit, and then one looks over at the other and goes: “What the hell is water?”

David Foster Wallace – This is Water

When writer David Foster Wallace gave a speech to the graduates of Kenyon College, he began by telling this story about the fish. His intention was simply to remind the audience that we all live in a reality that, by constantly surrounding us, ends up becoming invisible in the long run. And that we only notice it when it becomes something disruptive, an obstacle in our path: the driver who cuts us off at the corner, the clerk who demands yet another form to complete an application, the misspelled word: sapatilla, uevo, todxs. Meanwhile, the things we feel most certain about usually end up turning out to be those about which we are most mistaken. For example, Spanish:

All of us who were born and raised in the Spanish‑speaking world have quick, ready certainties about how Spanish works because it’s the language we intensely learned during our first years of life. And at some point we’re not wrong. Even if someone asked us what Spanish is, we could answer in a blink: “it’s our mother tongue.” But that answer wouldn’t really account for the true nature of the matter, because ultimately: what the hell is language?

So then, what the hell is language?

Just like the fish’s water, language is a bit of everything. Or rather, language is in everything, since once we acquire it, we never stop using it to think about the world around us. However, if we have to choose one definition among many, we’ll say that language is a social phenomenon. It always happens in relation to an “other,” a community with which we establish conventions about what words mean and how those words mean. In this sense, it’s worth saying that it belongs to all of us who speak it. And, in the case of the Spanish language, to the Real Academia Española (RAE).

Hold on! Why the Real Academia Española? It doesn’t seem very logical that the second most‑spoken language on the planet (after Chinese and before English) should be so jealously guarded by a few grumpy gentlemen. And it makes even less sense when you think that these gentlemen sometimes stand like Knights Templar defending something that nobody, absolutely nobody, is attacking.

Oh, really? Aren’t our young people like careless, rebellious fish? Aren’t they going through life with a scandalous linguistic promiscuity, writing ke, komo, xq or todes? Yes, many of them are. Readers will wonder how on earth we can allow such an outrage.

It turns out language is not a photo, it’s a movie in motion. And the Real Academia Española doesn’t direct the movie, it only films it. That’s what we call “descriptive grammar,” which is the work of delimiting an object of study (in this case, a linguistic one) and accounting for how it actually happens beyond the rules. That’s why, when a usage drifts away from what school textbooks indicate, if it’s used by a sufficient number of people and gains ground in certain spaces, the RAE ends up incorporating it into the dictionary. That’s its descriptive job. Then it informs the public and we all, horrified, raise the alarm because how can they accept “la calor” when it’s obvious, super obvious, that “calor” is masculine. It’s EL calor.

Does this mean we can do whatever we feel like with language? No. There are changes the system simply doesn’t tolerate. You can buy all the paints in the world and mix them as you please, but you can’t imagine a new color. Some parts of language work the same way: for example, it is not possible to conceive of Spanish without the subject category (the one we had to mark separately from the predicate in school, and when it wasn’t there we wrote “implicit” or “tacit” next to the sentence). Is it the Academy’s fault for not letting us? No, this time the poor thing didn’t do a thing; it’s the Spanish system itself that won’t let us. It’s simply impossible.

But then, if we can use language however we want and it’s still not going to break, why bother with the work of formulating rules and laws? Grammar that is not descriptive, the one that defines what is right and what is wrong, is called normative grammar and it exists for a reason: rules are necessary in order to analyze a language, systematize it, and teach it better to the next generations.

The important thing here is to understand that Spanish cannot be attacked, or that in any case it knows how to defend itself (it bends and adapts like a reed, little grasshopper) because it is in constant motion. Each generation believes that their parents’ language is pure and pristine, while their children’s is a degenerate version of it. But before we spoke Rioplatense Spanish we spoke another variety of modern Spanish. And before that, we spoke Cervantes’ Spanish, and before that the Romance languages that fermented after the dissolution of the Roman Empire, and before that Vulgar Latin and before Vulgar Latin there buzzed the Indo‑European languages and before that who knows what. The only thing we can know for sure is that the purest, most pristine, most primordial version of any language is some barely articulated grunts at the back of a cave.

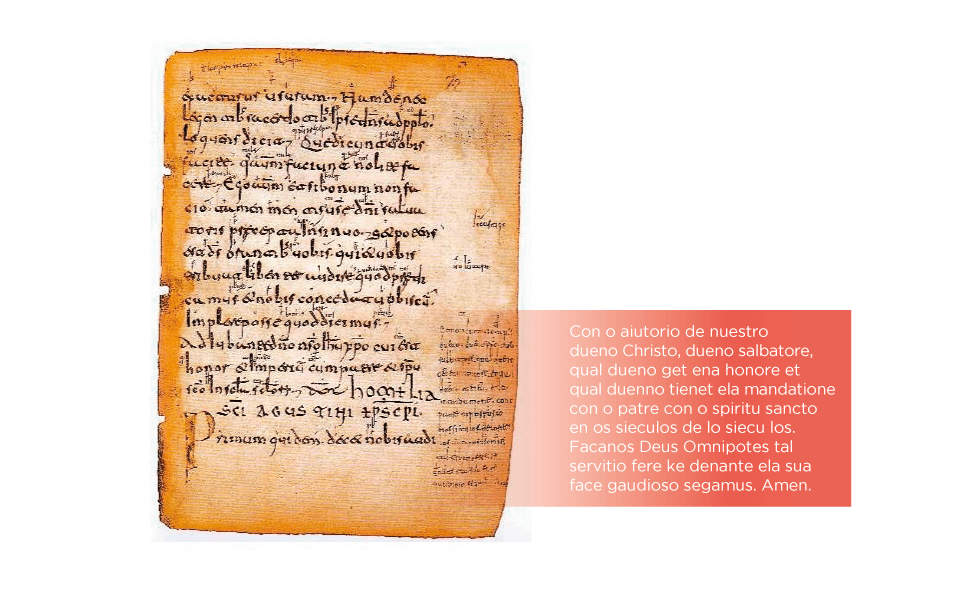

The Glosses of San Millán are one of the oldest records we have of Spanish. They are marginal notes in a Latin codex, made by monks in the 10th or 11th century to clarify some passage. As you can see on the side, thanks to the gloss now the passage is nice and clear.

Take the following curiosity as an example: the Spaniards who came to America during the Conquest still used voseo in its two forms: as both a reverential and a familiar form. They said “Vuestra Majestad” or they said, for example, “¿Desto vos mesmo quiero que seáis el testigo, pues mi pura verdad os hace a vos ser falso y mentiroso?” (because long live quoting Don Quixote). That “vos” took root in America, partly through literature and partly because Spaniards used it reverentially among themselves as a way of distinguishing themselves from the natives. Time passed and today millions of people use it without any kind of reverence or class distinction; however, voseo began to fall into disrepute in the 16th century in Spain itself, where Spanish settled on “tú” without anybody being particularly scandalized by it. Which shows that language is in constant change, but it happens so slowly that it gives us the feeling of being still. Getting indignant about that would be like the little fish in Foster Wallace’s story being outraged because the water —which they didn’t even know existed until just now— is getting them wet.

Now then, if at this point readers of this piece have accepted the basic notions about how the very language they’re reading works, it’s time to confess that this has all been part of an introductory ploy. It’s time to step through the looking glass and talk about a somewhat more controversial topic: inclusive language.

Welcome to the real article, dear readers.

The shapes of water

One of the most powerful capacities of any language is the capacity to name. Naming, categorizing, implies ordering and dividing. And from the moment we’re born (even before), people are divided into men and women. We are named in the feminine or the masculine; people refer to us using all adjectives in a particular gender. Long before our bodies have any possibility of taking on a reproductive role, we learn that being a man or a woman is different, and we identify with one or the other. Boys don’t cry, girls don’t play rough getting themselves all dirty. By the time we can answer “what we want to be when we grow up,” our preferences, self‑projections and desires already carry an enormous load of the symbolic schemes that surround us.

That immense social construction, built on the way society assigns importance to certain biological traits (in this case related to sexual and reproductive organs), is what the concept of “gender” refers to. What studies on the subject have theorized and documented is that the division into genders is not a neutral division, without hierarchies: on the contrary, the different characteristics and different mandates attributed to a person according to their gender in turn lead to inequalities that revolve, spoiler alert, around a predominance of male individuals.

Realizing that these inequalities have their counterpart in the way we speak is what led, several decades ago, to feminists and some academic and official spheres raising the importance of reviewing the use of sexist language. What is sexist language? It is naming certain roles and jobs only in the masculine; referring to the generic person as “man” or identifying the “masculine” with humanity; using masculine forms to refer to men but also to refer to everyone, leaving feminine forms only for women; naming women (when they are named) always in second place.

The undesirable consequences of this linguistic inequality translate into what sociologist Pierre Bourdieu defines as “symbolic violence,” and this helps us understand one of the mechanisms that perpetuate the relationship of male domination.

Symbolic violence has to do with our thinking of ourselves, of the world and our relationship to it, using categories of thought that are, in some way, imposed on us, and that coincide with the categories from which the dominator defines and enunciates reality. It is produced through the symbolic channels of communication and knowledge, and it succeeds in making domination seem natural. Its power lies precisely in being “invisible.” Again, like water, it becomes part of reality and we don’t even realize it’s there.

But the symbolic violence Bourdieu talks about does not constitute, as is sometimes misinterpreted, a dimension opposed to physical, “real,” effective violence. It is, in fact, a fundamental component for the reproduction of a system of domination in which the dominated do not possess any other instrument of knowledge than the one they share with the dominators, both to perceive domination and to imagine themselves. Or, rather, to imagine the relationship they have with the dominators.

Reversing this requires something like a “symbolic subversion” that overturns the categories of perception and appreciation in such a way that the dominated, instead of continuing to use the dominators’ categories, propose new categories of perception and appreciation to name and classify reality. That is, proposing a new representation of reality in which to exist.

Existing through language

But sociology is not alone in this: from the field of linguistics, in the 1950s a theory emerged proposing that language “determined” our way of understanding and constructing the world or, at least, shaped our thoughts and actions. This was the famous Sapir‑Whorf hypothesis.

For a long time, the idea that the language we speak could shape thought was considered, at best, unprovable and, more often, simply incorrect. But the truth is that the discussion remained mainly on the plane of abstract, theoretical reflection. With the arrival of our century, research on linguistic relativity resurfaced and, along with it, we began to gather evidence about the effects of language on thought. Different research teams collected data around the world and found that people who speak different languages also think differently, and that even grammatical issues can profoundly affect how we see the world.

All very nice, but what about the evidence?

To begin with, Daniel Cassasanto and his team found evidence, as a result of three experiments, that spatial metaphors (those like “the wait was very long”) in our native language can profoundly influence the way we mentally represent time. And that language can shape even “primitive” mental processes like estimating short durations.

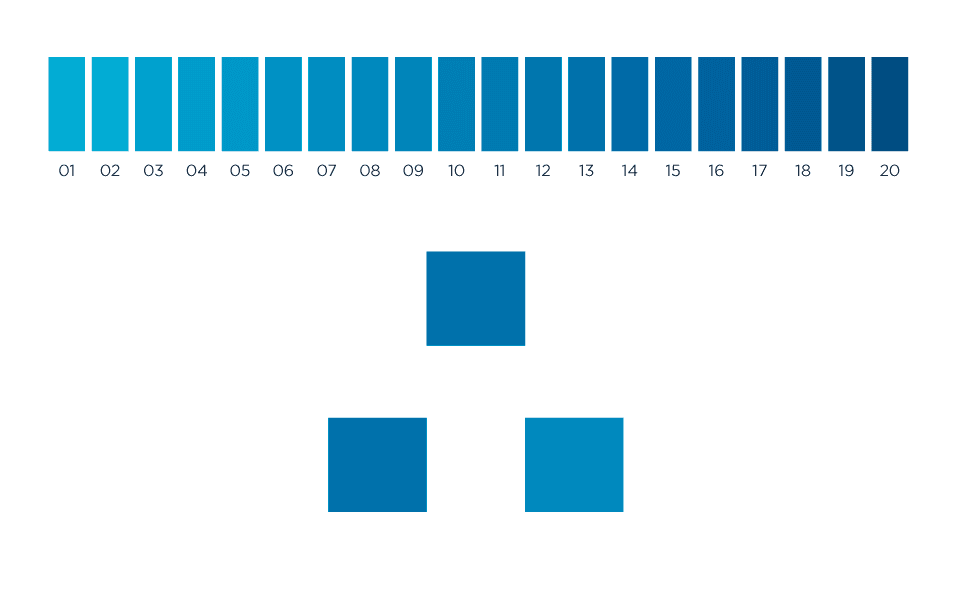

And they weren’t the only ones; other teams, like this one, this one, this one, this one and this one, found that the language we speak has a lot to do with the way we think about space, time and movement. On the other hand, a study by Jonathan Winawer and his team adds that linguistic differences also cause differences when it comes to distinguishing colors: it is easier for a speaker to distinguish one color (from another) when there is a word in their language to name that color than when such a word does not exist. Whoever wants light blue, has to say it.

At the top are the 20 shades of blue used in the study on the ability to distinguish colors depending on the language spoken by the participants. Below the complete palette we see an example of the task image: subjects had to choose which of the two squares at the bottom was identical to the one at the top. Based on Winawer.

But weren’t we talking about gender? Yes, yes, we’re getting there:

Supposedly, the gender of a word (masculine/feminine) does not always distinguish sex. It does in some nouns like señor and señora, perro and perra, carpintero and carpintera, which always refer to animate, sexed beings. But in general, gender in most words is not something that gets added to the meaning; it is inherent to the word itself and serves to distinguish other things: it distinguishes size in cuchillo and cuchilla (“knife/large knife or cleaver”), it distinguishes the plant from the fruit in manzano and manzana (“apple tree/apple”), it distinguishes the individual piece from the mass in leño and leña (“log/firewood”). In that case, they are considered different words and not variations of the same word. Other times, it doesn’t even serve to distinguish anything because many words exist only in the feminine and not in the masculine, and vice versa. In those cases, gender only serves to tell us how to use the other words that surround and complement that word. For example, “teléfono” exists only in the masculine. You can’t say “teléfona,” and yet we need that masculine to know that the phone is “rojo” and not “roja.”

So gender works in many ways in Spanish and not only as a binary system to decide whether things are for boys or for girls. But what really makes the issue interesting, no matter how grammatical we want to get in our analysis, is that gender in Spanish always carries a sexualized load, even when it refers to simple objects. No way! Or is there?

Yes, there is

Webb Phillips and Lera Boroditsky wondered whether the existence of grammatical gender for objects —present in languages like ours but not in English— had any effect on the perception of those objects, as if they actually had a sexed gender. To answer this, they designed some experiments with speakers of Spanish and German, two languages that assign grammatical gender to objects, but not always the same one (that is, some objects that are feminine in one language are masculine in the other). The results of five different experiments showed that grammatical differences can produce differences in thought.

In one of those experiments they sought to test the extent to which the fact that the name of an object had feminine or masculine gender led speakers to think of the object itself as more “feminine” or “masculine.” To do this, participants were asked to rate the similarity of certain objects and animals to human men and women. They always chose objects and animals that had opposite genders in both languages, and the tests were carried out in English (a language with neutral gender for naming objects and animals) so as not to bias the result. Participants found more similarities between people and objects/animals whose grammatical gender matched, in their native language, than between people and objects/animals whose gender differed.

In another study by Lera Boroditsky, a list was made of 24 nouns with opposite gender in Spanish and German, half of them feminine and half masculine in each language. These nouns, written in English, were shown to native speakers of Spanish and German, and they were asked for the first three adjectives that came to mind. The descriptions turned out to be quite closely linked to ideas associated with gender. For example, the word llave (“key”) is masculine in German. Speakers of that language described keys on average as hard, heavy, metallic, useful. Spanish speakers, on the other hand, described them as golden, small, adorable, shiny and tiny. Conversely, the word puente (“bridge”) is feminine in German and speakers of that language described bridges as beautiful, elegant, fragile, pretty, calm, slender. Spanish speakers said they were big, dangerous, strong, sturdy, imposing and long.

The results of María Sera and her team also found that the grammatical gender of inanimate objects affects the properties speakers associate with those objects. They experimented with speakers of Spanish and French, two languages that, although they usually agree on the gender assigned to nouns, in some cases don’t. For example, with the words “tenedor” (fork), “auto,” “cama” (bed), “nube” (cloud) or “mariposa” (butterfly). Participants were shown images of these objects and asked to choose an appropriate voice for them to come to life in a movie, choosing between male and female voices for each. The experiments showed that the chosen voice coincided with the grammatical gender of the word used to designate that object in the participant’s language.

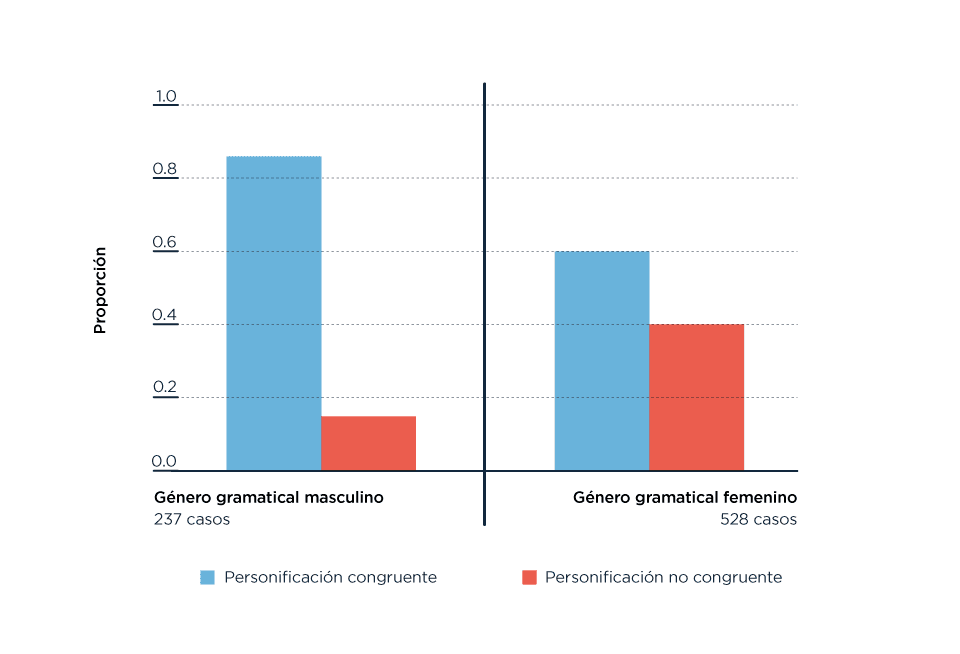

As if all this weren’t enough, Edward Segel and Lera Boroditsky also point out that the influence of grammatical gender on the representation of abstract ideas can be verified by analyzing examples of personification in art, in which abstract entities such as Death, Victory, Sin or Time are given a human form. Analyzing hundreds of works of art from Italy, France, Germany and Spain, they found that in almost 80% of these personifications, the choice of a male or female figure can be predicted by the grammatical gender of the word in the artist’s native language.

Snow White and the Seven Stereotypically Male Miners

So far so good: there is a relationship between thought and language, there is a link between gender and sex in speakers’ minds and there is evidence of it. But specifically, can language have an effect on the reproduction of sexist stereotypes and androcentric gender relations (that is, centered on the masculine)?

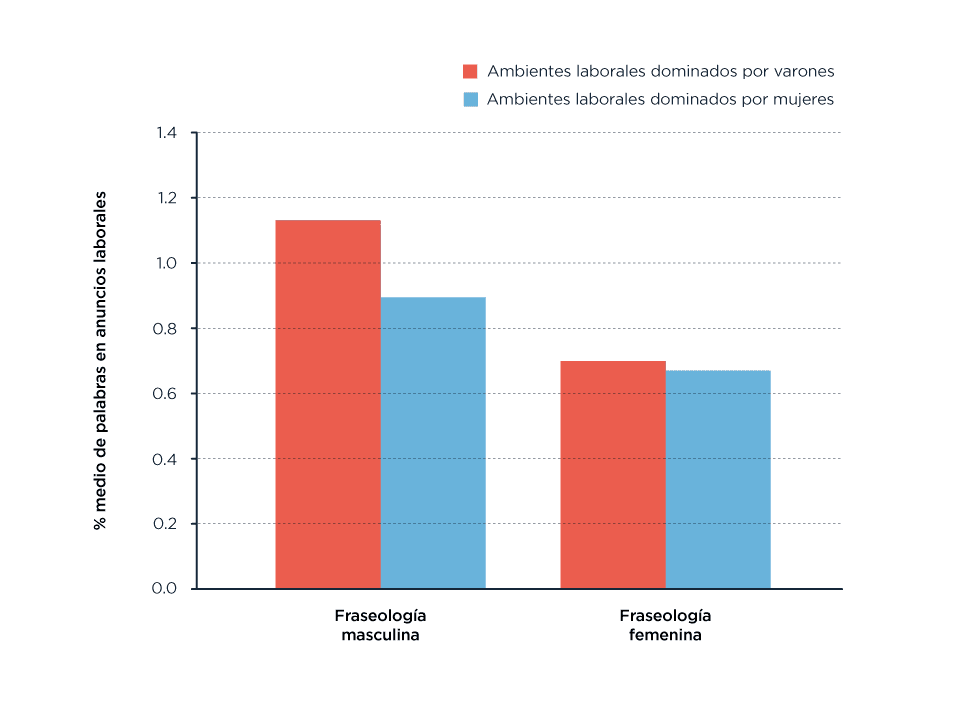

Well, yes. For example, Danielle Gaucher and Justin Friesen wondered whether language plays any role in perpetuating stereotypes that reproduce the sexual division of labor. To answer this, they analyzed the effect of “gendered” vocabulary used in job recruitment materials. They found that job ads used masculine phraseology (including words associated with masculine stereotypes such as leader, competitive and dominant) to a greater extent when referring to occupations traditionally dominated by men than in areas dominated by women. At the same time, vocabulary associated with the stereotype of the “feminine” (such as support and understanding) appeared in similar proportions in ads for occupations dominated by women and those dominated by men.

Job ads for male‑dominated occupations contained more stereotypically masculine words than ads for female‑dominated occupations. In contrast, there was no difference in the presence of stereotypically feminine words in both types of occupations.

They also found that when job ads included more masculine than feminine terms, participants tended to perceive more men in those occupations than when less biased vocabulary was used, regardless of the participant’s gender or of whether the occupation was traditionally male‑ or female‑dominated. Moreover, when this happened, women found those jobs less attractive and were less interested in applying for them.

Dies Verveken’s team conducted three experiments with 809 primary school students (between 6 and 12 years old) in German‑ and Dutch‑speaking environments. They investigated whether children’s perceptions of stereotypically male jobs can be influenced by the linguistic form used to name the occupation. In some classrooms, professions were presented in paired form (that is, with both feminine and masculine forms: engineers/engineers, biologists/biologists, lawyers/lawyers, etc.), in others in generic masculine form (engineers, biologists, lawyers, etc.). The occupations presented were in some cases stereotypically “masculine” or “feminine” and in others neutral. The results suggested that occupations presented in paired form (i.e. with both feminine and masculine titles) increased mental access to the image of women working in those professions and strengthened girls’ interest in stereotypically male occupations.

These are just some of the many studies carried out. If anyone is left wanting more, other studies (such as this one, this one, this one or this one) add evidence about how children interpret gender‑marked job or profession titles as excluding and how, in general, the use of a masculine pronoun to refer to everyone encourages the evocation of disproportionately male mental images. Or even how those not‑so‑generic generics can affect interest and preferences for certain professions and jobs among people in the group that “is not named,” leading them to self‑exclude from important professional environments.

So what do we do then?

Within this framework we can better understand the relevance of feminist efforts to introduce more inclusive uses of language. Many have been tried, starting with the slash to talk about los/as afectados/as, los/as profesores/as, los/as lectores/as. But this solution has some problems. First, reading stumbles over those slashes that jump out at the eyes like pins. On the other hand, it assumes that the multiplicity of human genders can be reduced to a binary system: either you’re a man or you’re a woman.

Other solutions were to include an x (todxs) or the @ sign (tod@s) instead of the gender‑marking vowel, but the @ sign was too disruptive since it does not belong to the alphabet and it also breaks the line in a way that’s different from other signs. The x, on the other hand, is still used but, like the @, it poses a major phonetic problem since no one is very sure how to pronounce it. Some people (for example, the writer Gabriela Cabezón Cámara) see an advantage in this: the disruptive element, what makes us uncomfortable, is precisely what draws attention to the gender problem that this use of language seeks to denounce; it’s the trace of a struggle, the mark of a challenge.

So far, the proposal that seems to have the best prospects for future incorporation without clashing too hard with the linguistic system is the use of e as the vowel to mark neutral gender. Since the goal is to stop referring to everyone with words that only name some, we don’t need to use it for absolutely everything; that is, we’re not going to start sitting on “silles” or taking “le colective” every “mañane.” But if we’re talking about people (or other animated beings to whom we perceive a gender identity), it offers us a possibility to speak in a truly inclusive way. In any case, this is not a problem‑free solution either: it implies, among other things, creating a neutral pronoun (“elle”) and a determiner (“une”). But stranger exceptions have been made and here we still are, eating almóndigas (meatballs) among the murciégalos (a playful, “wrong” version of “murciélagos,” bats).

Some of the voices that stomp and howl in indignation against these initiatives say that such proposals “destroy language.” And of course they appeal to authority: it’s incorrect because the Real Academia Española says so. But, as the reader already knows, what the Real Academia Española has to say on this matter doesn’t worry us in the slightest. With all due respect. Very nice dictionary.

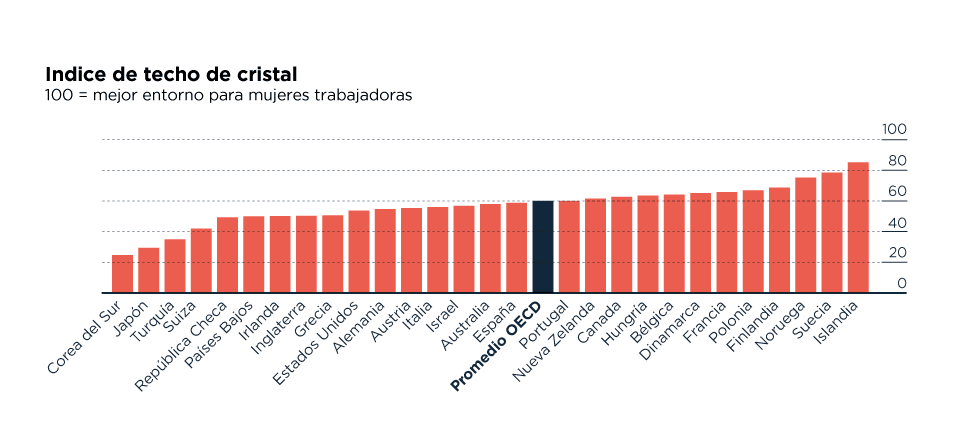

Another of the strongest resistances to this kind of proposal comes from those who simply deny that there is any relationship between language and greater or lesser levels of gender equity. Although we just mentioned empirical evidence suggesting that such a relationship does exist, people often refer to the equally empirical fact that in regions where less gendered languages are spoken —for example, with a truly neutral generic— we often find greater gender inequality than in other countries.

An interesting contribution in that direction is the work of Mo’ámmer Al-Muhayir, who compares Classical Arabic, Icelandic and Japanese, and shows that the sexism of a language does not seem to correlate with gender inequality. Classical Arabic uses feminine gender for plural nouns, regardless of the gender of that same noun in the singular. And yet it is one of the most conservative languages on the planet, and in more than one of the societies where it is spoken (such as Saudi Arabia or Morocco), it is hard to say that there is equality of rights between men and women. Icelandic, on the other hand, is one of the languages that has undergone the fewest changes over the centuries, remaining almost intact thanks to highly conservative language policies (they do not adopt foreign terms without first translating them somehow with Icelandic word roots), and it corresponds to one of the most advanced societies in terms of the place women occupy. And Japanese has no grammatical gender at all, yet this marvel of inclusive grammar exists in one of the most stereotypically machista societies we know.

However, empirical research offers indications that “neutral” nouns and pronouns in languages without grammatical gender distinction can still have a hidden male bias. Thus, although they avoid the problem of a male generic terminology, even neutral terms can convey a masculine bias. This also has the disadvantage that such a bias cannot be countered by deliberately adding feminine pronouns or endings, because those forms simply do not exist in those languages. This makes the kind of “symbolic subversion” Bourdieu talks about more difficult. That is the conclusion, for example, of Mila Engelberg’s work, based on her analysis of Finnish, a language that includes terms that are apparently gender‑neutral but in practice connote a male bias. And since it has no grammatical gender, there is no way to employ feminine pronouns or nouns to emphasize the presence of women. The author points out that this could imply that androcentrism in genderless languages might even increase the lexical, semantic and conceptual invisibility of women. Friederike Braun finds something very similar in her study of Turkish: the lack of grammatical gender does not prevent Turkish speakers from communicating messages with gender bias.

An Argentine hit song

No matter how many guidelines have been published for non‑sexist language use, at least when it comes to Spanish, the issue is by no means resolved. From linguists to everyday citizens, resistance comes in many forms. That it hurts the eyes, that it hinders speech, that it’s “correct,” that it makes you abandon reading the text, and the inevitable “it’s irrelevant.” That the real struggle should be focused on transforming “the real world.” That language only reflects “extra‑linguistic” relationships. That modifying language “by force” is only a matter of “political correctness” that diverts attention from the central problem and even masks it. But readers who have made it this far will have gone through half an article written in a traditional way and half an article written in inclusive language, so that, besides all the evidence presented about the relationship between language and thought, they can also assess how traumatic (or not) the experience has been, and ask themselves where the origin of this resistance really lies, of this desperation to preserve language intact.

Meanwhile, the dispute over language goes on. And of all the forms this problem can take, perhaps the most emblematic is the use of false generics, that is, exclusively masculine or feminine terms used generically to represent both men and women, as when we say “los científicos” (“scientists” in masculine): technically we could be referring to scientists (male, female, etc.), although we would also say “los científicos” if we only wanted to refer to male scientists. In contrast, we would only ever use “las científicas” to talk about those who are women.

Marlis Hellinger and Hadumod Bußmann explain that most false generics are masculine and that the only known languages where the generic is feminine are found in some Iroquois languages (Seneca and Oneida), as well as some Australian Aboriginal languages. In Spanish, even common‑gender nouns such as “artista” or “turista,” which remain invariable regardless of whether they refer to a man or a woman, end up marking the gender of what they name through the other words that complement them (adjectives, articles, etc.). So, again, to refer to mixed groups, we resort to the gender that names only men. Perhaps the only genuine generics we have are the so‑called epicene nouns such as “persona” (“person”) or “individuo” (“individual”), which not only remain invariable (there is no “persono” or “individua”) but don’t even allow gender marking in the adjective (because even if a person is a man, he will never be “persona cuidadoso,” nor will a woman ever be “individuo cuidadosa”).

But just like we mentioned above, a generic with a macho bias can represent an even more difficult problem to make visible and “subvert.” An Argentine hit in this sense is the debate over the word “presidente” (“president”):

A piece by Patricia Kolesnikov recalls a brief dialogue at a dinner table, where a gentleman was explaining why it’s wrong to say presidenta. The gentleman’s grammatical reasons were unassailable: “Presidente is like cantante. Although it looks like a noun, it’s another kind of word, a present participle, or what’s left of Latin present participles. A word that indicates the one who performs the action: the one who presides, the one who sings. It simply has no gender. Are you going to say cantanta?” Kolesnikov says there was a moment of doubt at the table, until the writer Claudia Piñeiro, with the wisdom of a fish that knows the water, replied: “And do you also not say sirvienta (maid)? Or is it that presidenta no, but sirvienta yes?”

Anecdotes like this remind us that language is malleable and that supporting or rejecting a disruptive usage, one that aims to claim rights long and unjustly denied, is a political decision, not a linguistic one. That if we are striving for a more equal world, language is not a magic key to achieve it, but neither can we deny it as a battleground. And that while femicide statistics rise and the average wage of women workers remains below that of men, it might be best not to get too outraged if someone smudges the pristine white walls of language just a tiny little bit.