and that nevertheless cannot be contained in words

thought in concepts

cannot even be remembered as it is.

It is what it is, and it is not mine, and sometimes it is in me.

Mario Levrero, The Empty Speech (1996)

In one of the first chemistry courses I took at university, I had one of those classmates who ask everything and for whom no answer is good enough. One day he asked: What is an atom really like?, to which Marcos, the TA who was giving the class, replied: The atom is what it is. In other words, he told him to stop asking in a diplomatic way. This classmates insistence on finding a truer truth is an example of something fundamental that happens in many scientific developments: we need to put a face to something we cannot see, something we try to understand without fully knowing it. Like the idea we form of someone we only know on the Internet, built as a superposition of the photos they posted on their profile on some social network.

Throughout history, many people tried to imagine what an atom was like using information they obtained indirectly because looking at it was impossible (until not long ago). Those mental images they came up with, and that managed to explain the results of their experiments, are what we call atomic models. But the truth is that the atom was, is and will be nothing more and nothing less than what it is, as Marcos told us. This is very similar to the because I said so we tell a 4-year-old child faced with their tedious Why?, why?, why?. But of course, that because I said so often doesnt satisfy the little inquisitor, and even less so us, because it is the classic non-answer. We need something solid. Something that explains a bit more. But careful: that explanation is going to be put to the test over and over again. Because no matter how good it is, it wont be the ultimate, final truth. It will be a model, an approximation. And if it survives, say, almost a hundred years, we can trust that it is a very good one.

Indivisible

The best we know today in terms of atomic models started to take shape around 1900 and was finally fleshed out with the emergence of quantum mechanics some thirty years later. But before that, long before, Democritus and others in Greece had proposed the existence of something very small: the tiniest portion of matter. And they called it atom, which means indivisible. Although today we know that atoms are divisible because they are made of smaller particles, it is also true that when we talk about a compound, for example a molecule, atoms are its fundamental part from a chemical point of view. Now then, what does an atom look like? Did people always imagine it had the same look? How did they figure out it wasnt so indivisible? How did they manage to give it a face similar to the one it has for real?

We cant go on talking about atoms without talking about elements. If we go back to Greece, it turns out that Democritus idea was overshadowed by another one that occurred to Empedocles, who claimed that matter was made up of 4 fundamental elements: earth, air, water and fire. Aristotle supported this idea, and since it is said he had a lot of influence back then, people decided to set aside the idea of the atom for a modest twenty-four centuries. Only around 1780 did Antoine Lavoisier appear, a French scientist who, thanks to his significant financial resources, was able to study a huge number of chemical reactions. Antoine worked side by side with Marie-Anne Pierrette Paulze, also known as madame Lavoisier, or the mother of modern chemistry. They did so many experiments that they realized there were not just 4 fundamental elements, but 55. For example, by studying the composition of water they saw that there was more than one thing in there and therefore it wasnt as fundamental as was assumed. That is how they ended up naming for the first time oxygen and hydrogen. Their studies also gave rise to the famous phrase nothing is lost, everything is transformed, which is all very nice in terms of conservation of mass, but when I said it to one of my ex-boyfriends, he started crying. Lavoisier ended up quite a bit worse than my ex: he was guillotined, to the sound of the Republic has no need of scientists. The vintage European version of go wash the dishes.

It is perhaps curious that the first person to retom the idea of Democritus atom after so many centuries was someone we surely know much more for color blindness than for his atomic theory. Around 1800, John Dalton asserted, among other things, that matter was made of atoms. He was still convinced that the meaning of the word was correctthat is, that the atom was the smallest and indestructiblebut in addition he said that atoms of the same element have the same properties and the same mass, and that these are different from those of another element. He also said that these atoms are the ones that combine to form compounds. He concluded all this and more after studying how different gases reacted with each other, on the basis of which he drew up the first table of relative atomic masses for some elements. Except for the indivisible part, he nailed everything.

Close, but no, Dalton.

Not so indivisible

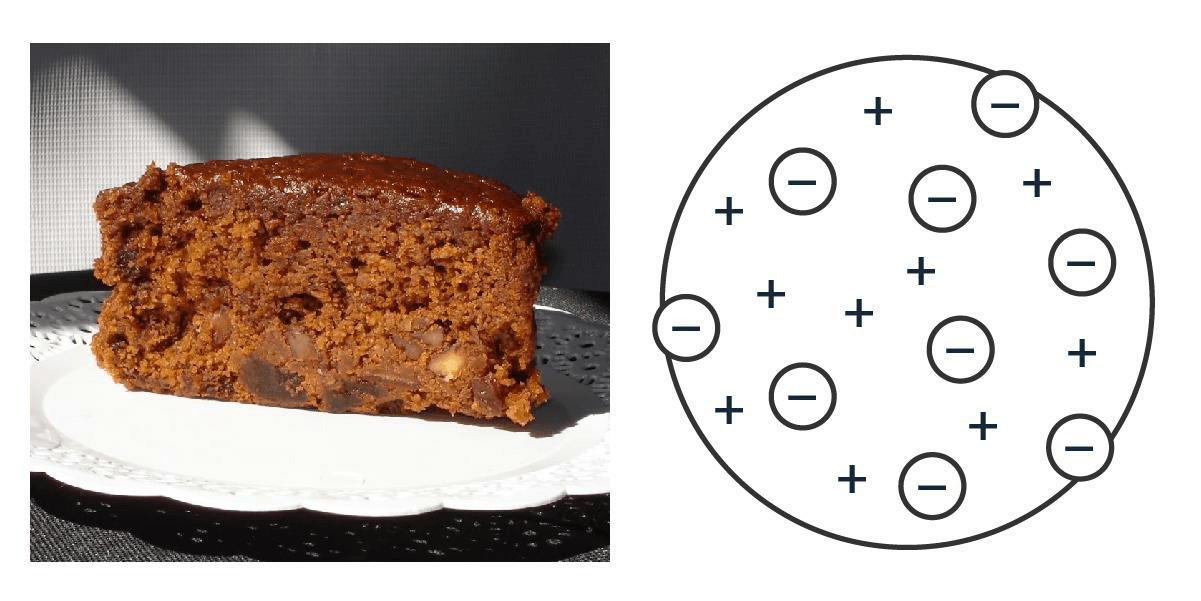

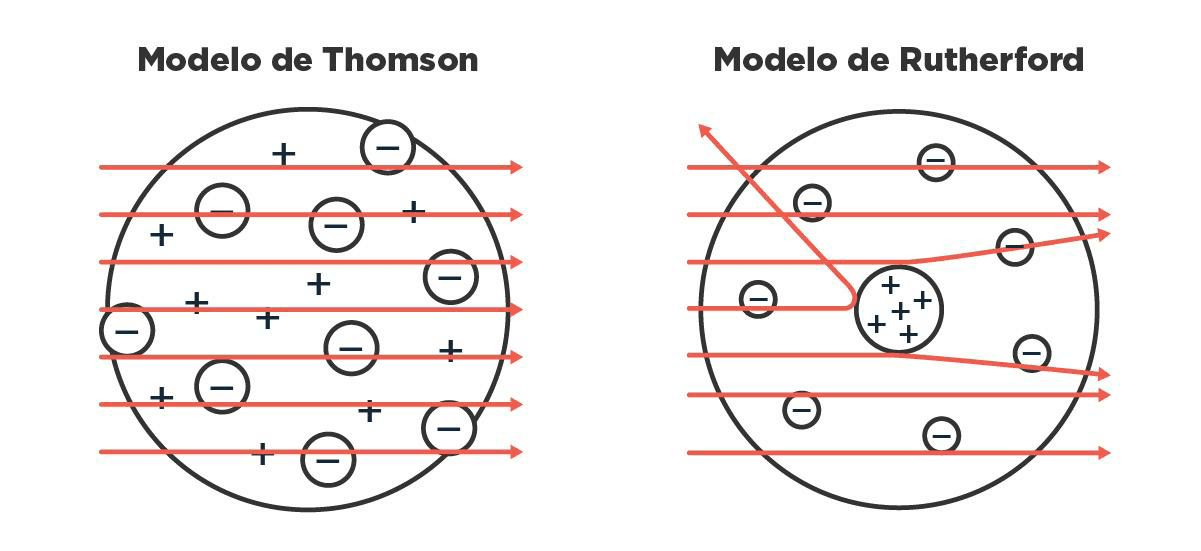

A hundred years later, J. J. Thomson started playing with cathode rays (the ones in old TVs) and, by gutting atoms, proposed that inside them there was something smaller that shot out, some negatively charged particles he called corpuscles and that we now know as electrons. Voilà: the atom is divisible. Since it was already known that the atom is neutral, to compensate for those negative charges something positive had to be added. J. J. imagined that electrons were like nuts uniformly distributed inside a cake whose batter was all positive. Very English, for people for whom fruitcake and five oclock tea are almost a religion.

The famous English tea with atom.

It is remarkable that, almost at the same time, Marie Curie noticed that the spontaneous emission of particles from uranium, or the rays of uranium as she called them, made the surrounding air conduct electricity. What is striking is that she said that this radiation came from inside the uranium atom, which also meant she was asserting that the atom could be split. But there were still a few years of feminist struggle left before they began to recognize her observations.

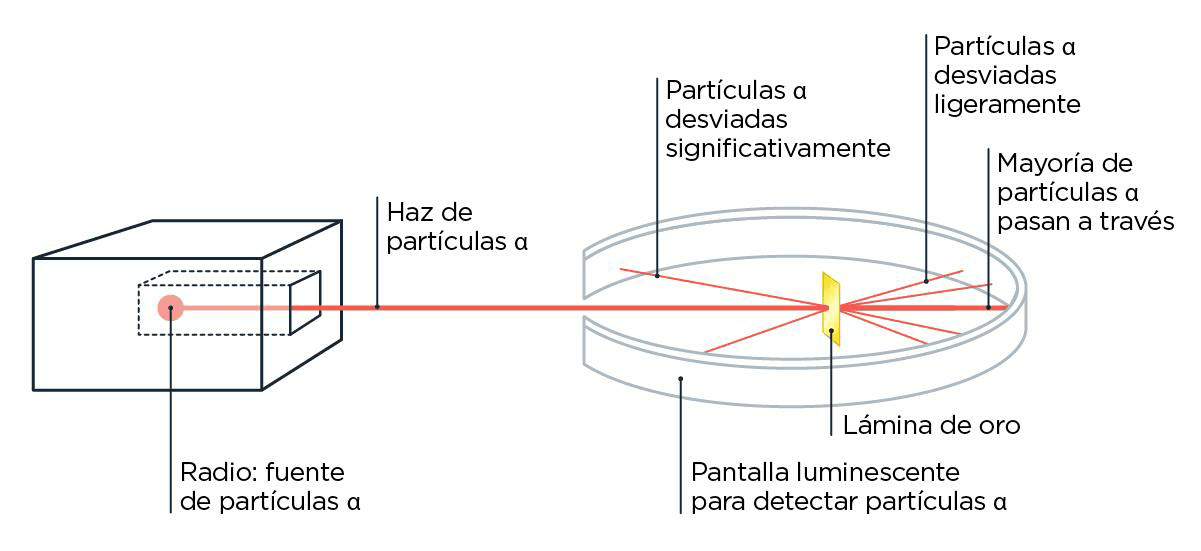

Ernest Rutherford, a student of Thomsons, continued analyzing this matter of particles that naturally shoot out of certain elements, today better known as radioactivity. After several experiments in which he made those particles collide with things, he named them according to how much they could penetrate: he called them, in increasing order of penetration, alpha, beta and gamma radiation. Rutherford was already kind of tired by then, so after the German physicist Hans Geiger visited him in his lab in Canada, he suggested that Geiger continue experimenting with some ideas he had been considering. Geiger and his student Ernest Marsden then began playing with the alpha particles, the least penetrating ones which, besides being the most sluggish, had the peculiarity of being positively charged. What they saw, to their great surprise, was that some of those particles were deviating a lot from their path when they made them collide with a very thin gold foil. If gold atoms had all their charge spread uniformly in space, as J. J. proposed in his cake model, all the alpha particles should have gone through them without deviating too much. But no, some came back almost in the same direction: they bounced.

What did one alpha particle say to a gamma particle? When you went, I had already gone and come back.

These observations led them, and Rutherford in particular, to a hugely important conclusion: the atom has a lot of charge concentrated in some region. Rutherford proposed that it was positive and, moreover, that it was in the middle, with the negative corpuscles around it. He called that center of positive charges the nucleus and the particles that gave it that charge he called protons. Thus the idea was established that the nucleus was a positive point in space that contained almost all of the atoms mass, and that there were negative charges orbiting very, very far away. Between the nucleus and the electrons, a huge emptiness.

What should happen to alpha particles when colliding with an atom according to Thomsons model versus what really happened, and how Rutherford solved it by putting the charges in different places.

As beautiful as it was, Rutherfords proposal of this atomic model kicked up quite a fuss in the scientific community. They said everything to him except that it was nice:

Rutherford: So, as I was saying, the atom has a lot of positive charges all together in the middle.

Absolutely everyone else: Wait, wait, wait… are you telling us there can be charges of the same sign all crammed into the same place? Are you crazy, man?

All of this bothered even him: it was very difficult, not to say impossible, to explain at that time how there could be a center full of particles with the same charge that did not strongly repel each other. It wasnt until ten years later, when the existence of the neutron was discovered, that these issues got an answer. But how? The idea proposed was that neutrons stabilize atomic nuclei and act as a sort of moderator among so much positive charge. In addition, it was postulated that everything stays glued together thanks to some crazy forces called nuclear or strong forces, which, unlike gravity (which is one of the weak forces), act only at VERY short distances. And since everything has to have an associated particle, the carrier of this force was named the gluon, from English glue. Much later it was found that both protons and neutrons are themselves made up of other particles, the quarks. In the end there were so many subatomic and subnucleonic particles (I neither deny nor confirm the existence of this word) that the whole collection is now known as the particle zoo. I swear.

Returning to Rutherfords model and the mess it caused, we were still missing the whole issue of the electrons. Where were they?

Rutherford: Well, they must be in perpetual motion, orbiting around that nucleus… right?a0

Absolutely everyone else: The laws of physics tell us that if there are charged things spinning around, it is inevitable that they lose energy, so eventually they should slow down and thus collapse onto the nucleus tracing a murderous spiral. That cannot live indefinitely, nothing would exist due to the collapse and this conversation would be eternally introspective and imaginary.

Although Rutherfords model could not answer all the questions (as almost always happens), it was the only one proposed so far that could explain Geiger and Marsdens experiment.

A story with spectra

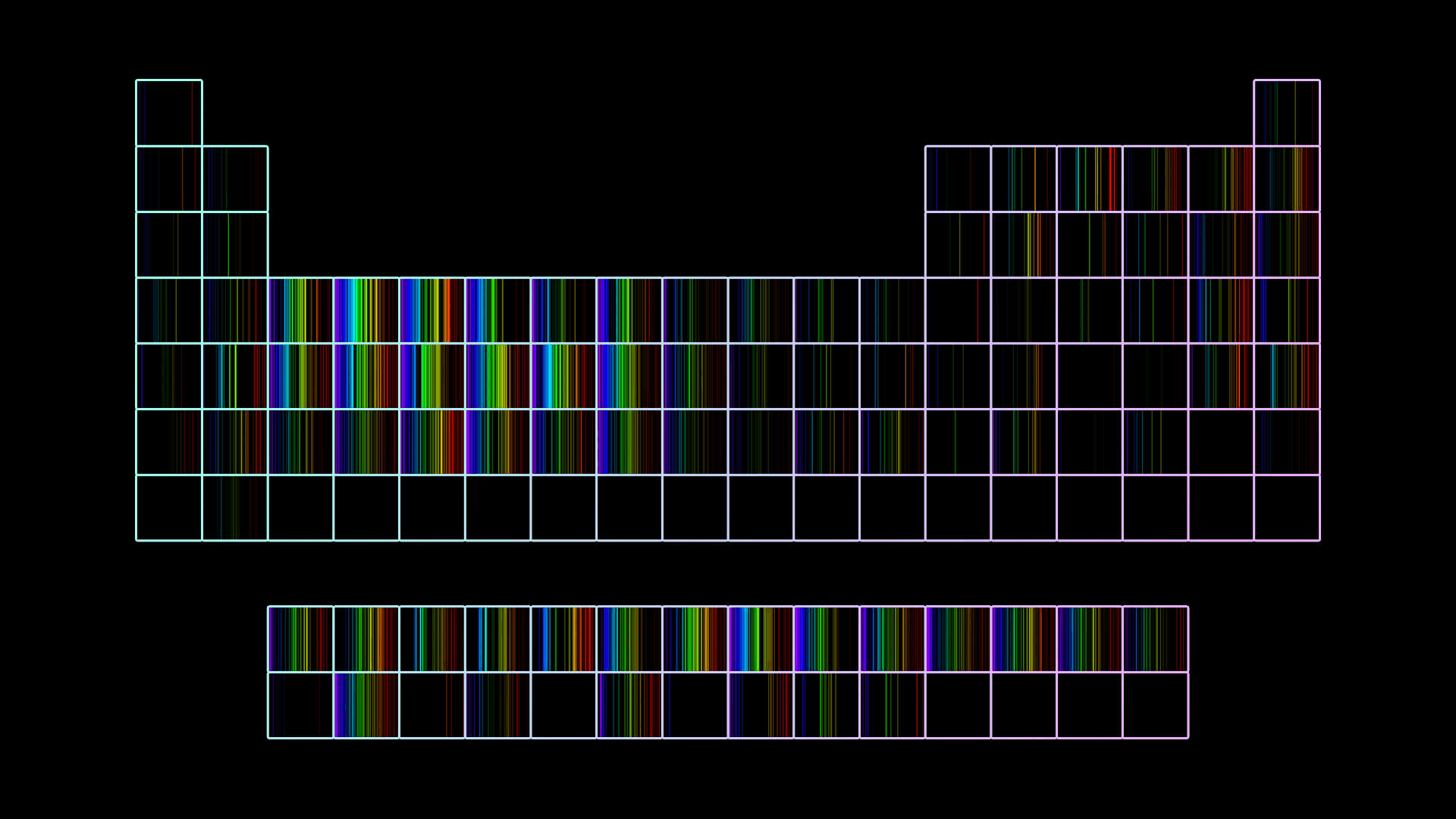

To answer where the electrons are, we have to go back a bit in history. We have to learn a couple of things about colors and elements, the things Dalton could not see. Around the time of the fruitcake model, different people noticed that when they heated some elements intensely, very specific colors of light came out. Moreover, they realized that each element had a color fingerprint. Color is synonymous with energy: the closer to violet, the more energy the light has; the closer to red, the less. They called those fingerprints spectra.

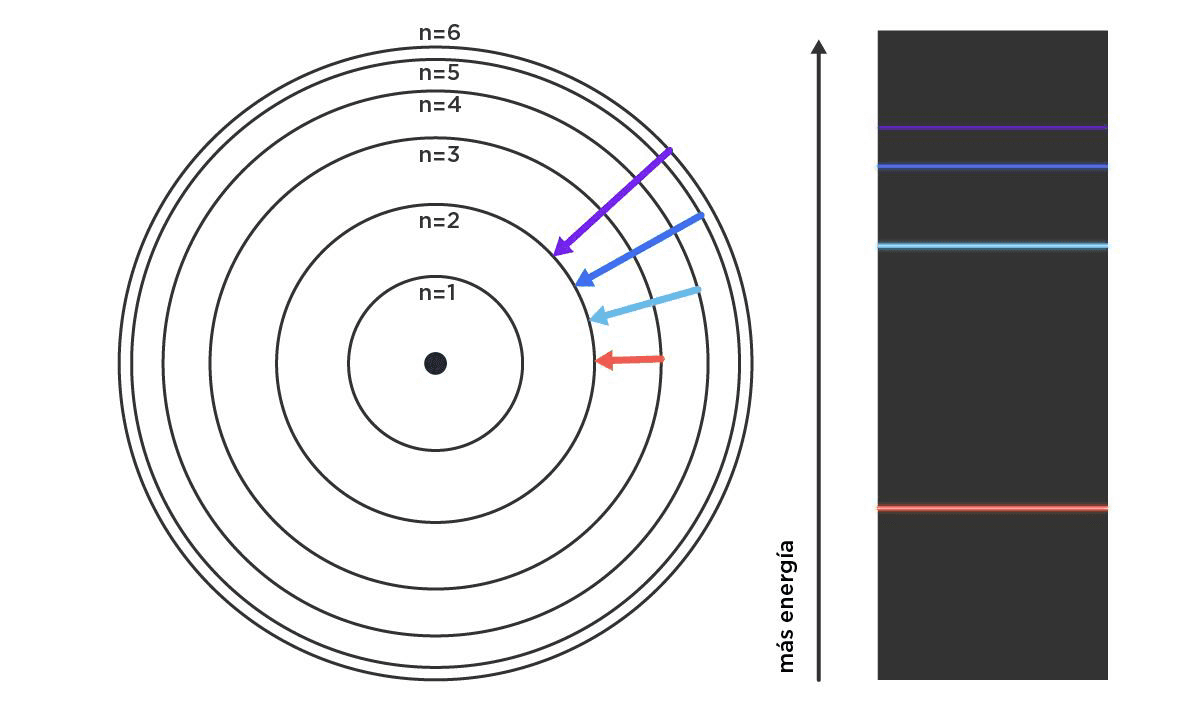

Emission spectrum of the hydrogen atom: colored lines that represent different energies, as a consequence of the electron jumping between places of higher energy (reached after heating the atom) and those of lower energy.

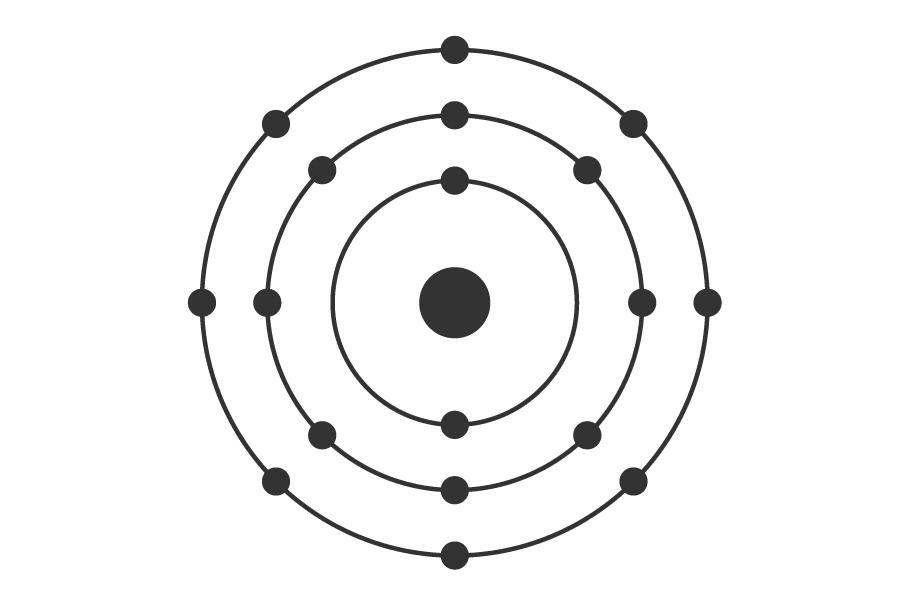

All this was in itself very beautiful, because it represented a very powerful tool for identifying elements, but it was even more beautiful when Niels Bohr proposed a new atomic model that explained these observations. The novelty was to propose that electrons, which no one knew very well where they were but certainly not stuck to the nucleus, had to occupy specific orbits (which in turn establish certain energy levels), and those orbits had to be at very well-defined distances from the nucleus, with a maximum number of electrons per orbit.

According to Bohr, this would be a lovely argon atom. Note that the relative size between the proton and the electrons is not to scale. Nor is the relation between the size of the nucleus and that of the entire atom, which is ~20,000 times larger than the nucleus.

By then, Max Plancks formalism, a pioneer of quantum mechanics around 1900, was going strong. Based on his ideas, Bohr established allowed and forbidden places for electrons. Electrons could jump from one orbit to another, but they could not live in between. Those jumps were associated with quanta of energy, that is, very specific amounts. We can think of a hopscotch game: if we want to get to heaven from earth, we have to make specific jumps. We cannot drag our feet, and we cannot touch the lines, because we lose. This model was arbitrary in a similar way, with rules as clear as they were inconsistent, but it served to explain the idea of spectra as a fingerprint. How? Those packets of energy are characteristic for each element, and when they come out in the form of light, they translate into a color. The simplest case (and the only one Bohr could truly predict) is an atom with only one proton and one electron, or rather, the hydrogen atom. What Bohr was proposing was that this single electron of hydrogen in its ground state, that is, without any disturbance, will live in a circular orbit at a specific distance from the proton, with a determined energy. But if we heat it a lot (a way of giving it energy), it will be able to occupy other, more distant orbits whose associated energies are higher. Moreover, the difference in energy between one orbit (level) and the original one has very well-defined values, that is, colors, which allow us to unmistakably identify hydrogen when it emits light as it cools. This is how many new elements were found, including helium, because looking at what color comes out of a hot rock in the lab is a lot like looking at the sun.

Graphic description of the jump of the hydrogen atoms electron from different energy levels to the second level, and the colors associated with those jumps.

Each element has a very specific spectrum associated with it.

Bohrs model was one of the first to successfully explain many things at once, among them several of the properties that make elements arrange themselves in the periodic table as they do. But (there is always a but) it failed in some important aspects, increasingly difficult to get around. Everything became quite complicated when trying to predict the behavior of elements with more than one electron. For example, it couldnt explain the presence of very similar-colored lights (double lines), which was a sign that two electrons that in theory were in the same orbit in fact did not have the same energy. Worse still: the model could not accurately predict which colors the heaviest elements emit. These complications were partially solved a couple of years later, when Arnold Sommerfeld added two relativistic patches to the model which, among other things, established that from the second energy level onwards (the second orbit from the nucleus) the electron can also inhabit sublevels.

In addition, the model imposed a very specific motion for the electrons, which would allow us to know exactly where they were at a given moment. Over roughly ten years there were several back-and-forths in which people proposed that electrons were particles but behaved like waves and vice versa. In the words of Louis-Victor de Broglie: All matter presents both wave-like and particle-like characteristics and behaves in one or the other way depending on the specific experiment.a0Only around 1925 did Schrödinger appear on the scene and throw at us a bunch of (wave) equations that brought some relief to so much contradiction. To these equations was added Heisenbergs proposal, which stated that it is impossible to measure simultaneously and with absolute precision both the position and the velocity of a quantum particle, a concept better known as the uncertainty principle. This has to do with the fact that trying to measure quantum things gets tricky because we dont have tools that are smaller than what we want to measure. Or, in plain language, its like trying to play the piano with an anvil. That being said, Bohrs idea of electrons going round in circles in defined orbits no longer made much sense: we cannot trap an electron exactly where it is, because if we try, we are going to break its quantum state and what we will measure will be a mixture of what it was and what we caused by trying to measure it.

Little houses

Between 1925 and 1930 many things happened that pointed toward a happy ending: the most realistic description of atomic structure known to this day. In fact, the greatest contribution lay in describing the distribution of electrons in space in a very concrete way that was consistent with experiments. With absolutely all of them.

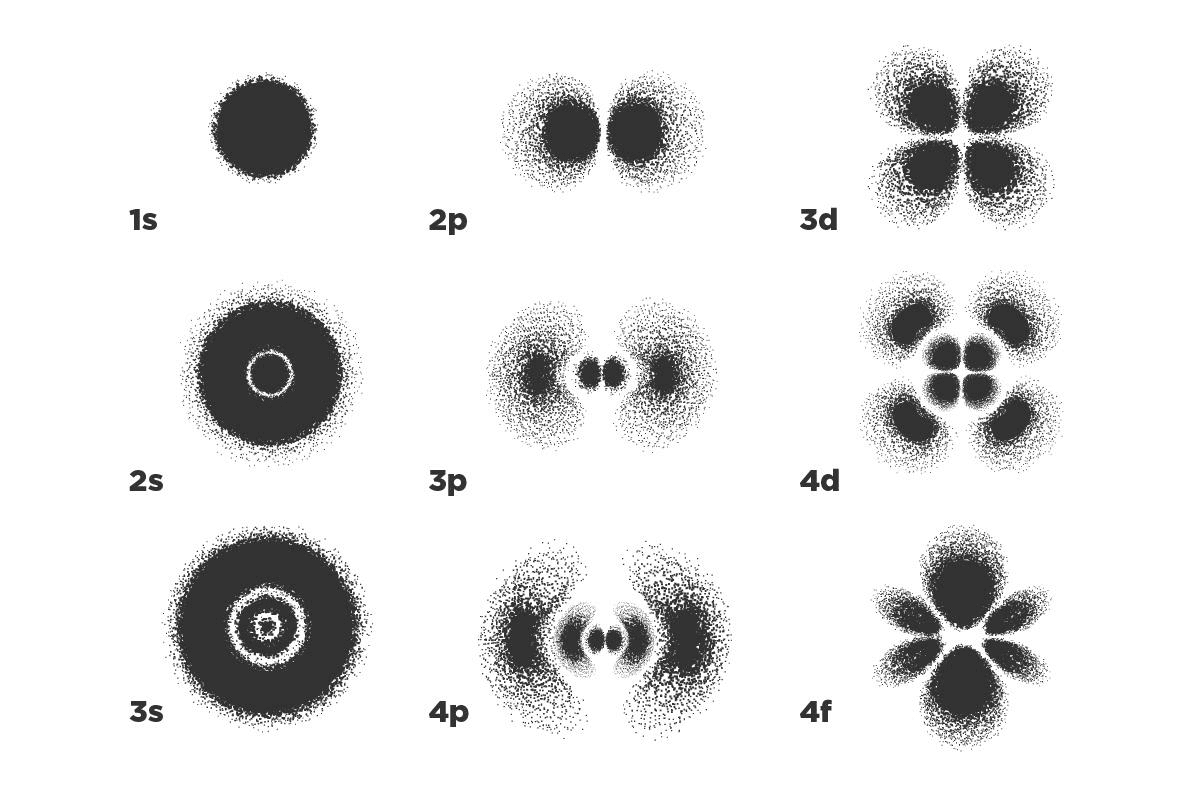

This complete and consistent description involves introducing the concept of an orbital. An atomic orbital is an equation that represents the probability of finding electrons in a particular region of space. These regions can be thought of as clouds with very characteristic shapes, given by the specific energy level they represent. The electron is not here or there, it is somewhere that could be anywhere in space, but with a probability that changes depending on the type of orbital. That probability is a number: close to 0% if the electron is almost certainly not there, and close to 100% if it almost certainly is. Only when summing the probabilities over all space do we get 100%, that is, we are absolutely sure the electron is somewhere (super informative, right?).

Orbitals are very far from being the circular or elliptical orbits proposed by Bohr and Sommerfeld. Aside from not representing a defined place in space where the electron will definitely be, as Bohr said of orbits, those probability functions can have very weird shapes.

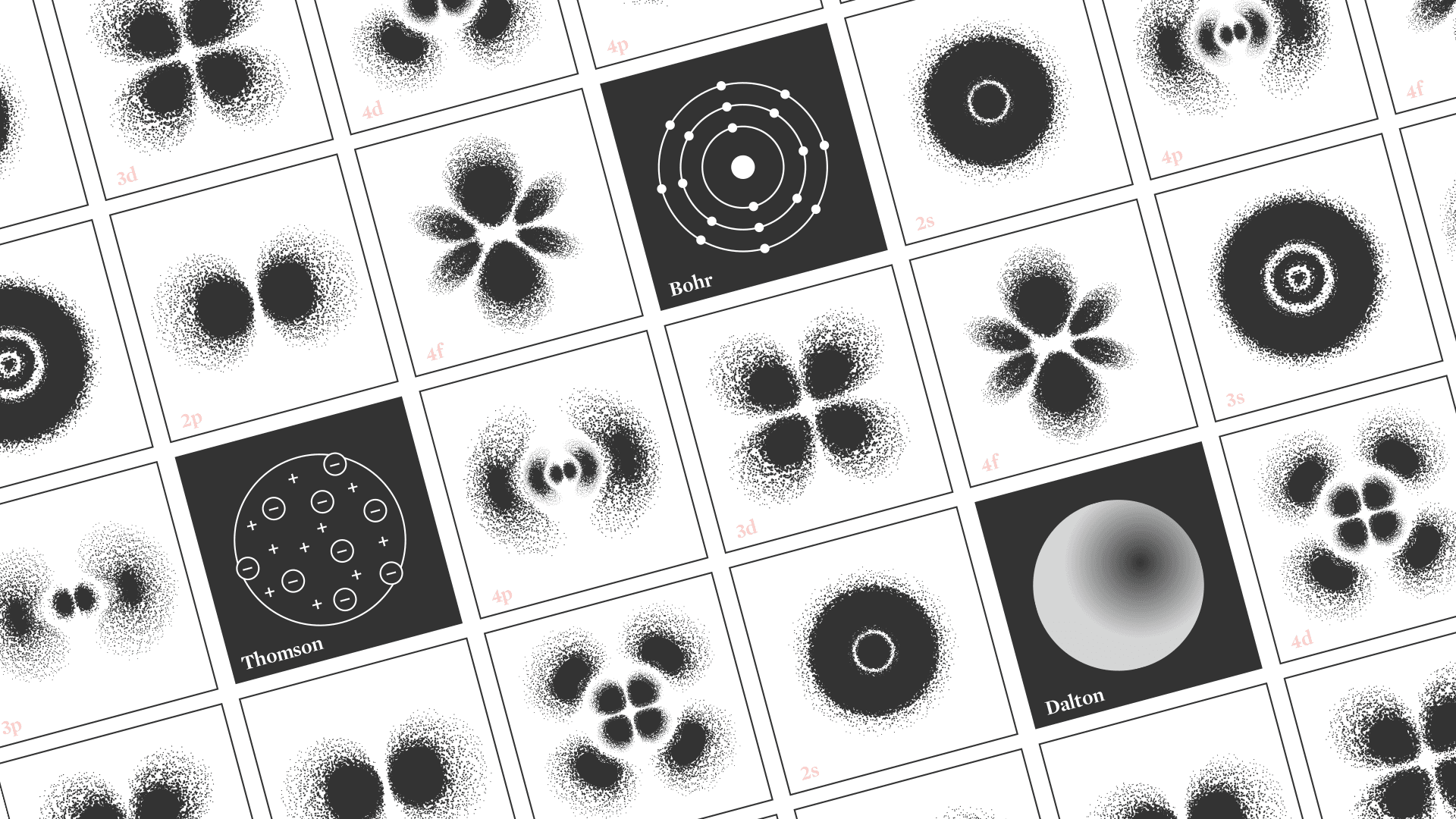

Probability distributions of finding the hydrogen electron for different orbitals, that is, for different energy levels. The darker it is, the more likely we are to find it there, while the number tells us about the energy level (1 is lower than 4). The letter has to do with the shape of those orbitals, and the origin of each letter comes from how the lines look in spectra: s from ‘sharp’, p from ‘principal’, d from ‘diffuse’ and f from ‘fundamental’.

Hold on a second: doesnt hydrogen have only one electron? Why are there many places where it could be? Well, because precisely what is super interestingand at the same time complexis that this electron can have (under certain conditions, for example, if we shine light on it) the possibility of jumping up to other orbitals. This is analogous to what we were talking about before, about taking electrons to higher energy levels by heating them. Because, ultimately, an orbital is also energy. That is, we can imagine an atom without its electrons as a brand-new building with little homes ready to be occupied. And those little homes are the orbitals. This is known in the nerd world as a hydrogen-like atom.a0

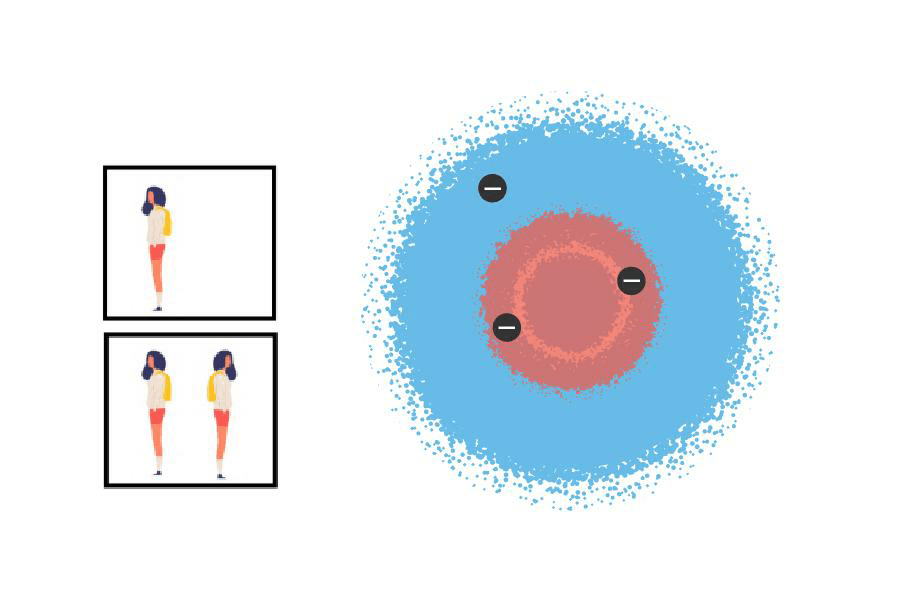

As if nothing, we have arrived at the exact mathematical description of an element that has only one electron. However, if we try to understand in an ultra-exact way other, fatter atoms, the math gets quite complicated. There is an approximation that saves us, which consists of filling the orbitals with electrons one by one, from those with the lowest energy to those with the highest (this is called the orbital approximation). But there is a very strict rule that electrons cannot avoid by the very fact of being electrons: each little home can only be occupied by two of them, and electrons kind of have to face in opposite directions. In particle physics, it is well known that there are few things more difficult than coexistence between electrons. The point, then, is that if we want to imagine, for example, what lithium is like (hint: three electrons), we can think that two electrons live in the first little home (the lowest-energy one) and that the third electron has no choice but to go to the next little home, which has more energy, and thus be located farther from the nucleus. This approximation is super useful for understanding that if we look closely at the periodic table, what we have is simply a succession of slots from left to right in which electrons are added one by one (which is the same as adding protons, because for a long time we have known that atoms are neutral). So it is as if we were progressively occupying more of those orbital-little-homes to form a big block of apartments.

Electrons of lithium in their little homes: two in the pink home (orbital 1s) and one in the blue home (orbital 2s). You cant see them, but believe me: the ones in the pink home are facing in opposite directions; difficult coexistence.

The best weve got

My inquisitive classmate from the beginning would be very upset if at this point I didnt say that we can always split hairs finer and finer and build more and more exact models. Schrödingers model is almost perfect, but it is not the best of all. The heaviest elements, with more electrons, require us to consider crazy effects related to those electrons moving at speeds very close to that of light. That ultra-complete model is known as the relativistic quantum model, it was developed by Paul Dirac, and that one really is the best weve got (at last!). Note, lets remember that these last models weve been discussing focus on describing electrons, but the nucleus is also mega important.

Our best mental image of the atom involves, on the one hand, a positive nucleus made up of protons and neutrons glued together thanks to gluons, which holds almost all the mass. On the other hand, that nucleus is surrounded by a cloud of electrons that live in pairs and turn their backs on each other, in orbital little homes with crazy shapes, far from that zoo of nucleonic particles, and farther away the more energy they have. The electron part is enough to do chemistry, that is, to explain how atoms react to form compounds or whether they end up staying alone. If we look at the nucleus, we can understand, for example, how and why some atoms break into pieces spontaneously and where the energy comes from (or where it goes) when that happens.

Ultimately, after getting to know the atom a bit better and sailing through its history, we might fall more in love with it than with the superposition of its virtual photos. Now we understand better why it is what it is, in its completeness and complexity. Now we know it has a big, very big, positive heart. And on top of that, with those electrons around, theres surely a lot of chemistry going on.