1/ The future

March 5th, 2030, the alarm is going to go off in two hours and I’m writing to make the time pass. I haven’t slept a wink all night. What’s going to happen this afternoon excites and terrifies me in equal parts. At 8:30 I have to be in Parque Saavedra, jogging as if I lived nearby and hadn’t done four kilometers to get there from my house in Vicente López. When I’m going past the carousel, I’ll have to pretend I twist an ankle and sit for a while on the grass, getting out of the way of all the people doing their mandatory daily hour of aerobic exercise. Someone is going to come over to help me, I don’t know if a man or a woman, old or young, they only assured me I should stay calm, that they will show up. While they check my supposed sprain, I have to pay them. And then, he (or she, or they, I don’t know) is going to tuck an alfajor into my sock.

They assured me they’re discreet. Nobody’s going to notice. My ankle is going to look like Diego’s in ’90, but with socks. It’s essential that I wear high socks, they repeated it to me more often than the price of the alfajor.

My plan afterwards is to limp a few blocks to Camila’s house, she lives nearby and she’s the one who gave me the lead. Camila swears that this people’s alfajores are exactly the same as the Terrabusi ones they used to sell at kiosks, back when you could still sell alfajores at kiosks, when there were still kiosks. I’m suspicious, not because I think she’s lying, but because it’s hard for me to accept that she has the memory of the taste so vivid, while mine has already started to fade.

I count once more the bills on my nightstand: I want to have the exact amount so the exchange is quick and we don’t waste time or raise any suspicion. Next to them I see the jar of weed I bought yesterday at the supermarket. I don’t know how long it’s been since I last bought any, I hardly ever smoke anymore, but everybody knows the tastiest alfajor you can eat is the one you have when you’ve got the munchies.

2/ The place where ideas go to radicalize

Few realities seem less appealing to me than one in which we can’t buy alfajores with total freedom. And besides being unappealing, it also seems impractical: we already know that banning consumption doesn’t stop it, it just turns it clandestine. The question I ask myself, the one that has me sketching scenarios in my mind, is really another one: is such a reality feasible? Is there a possible, probable future in which alfajores end up on the dark side of the law?

On Twitter, the place where ideas go to radicalize, there are people who think the Front-of-Package Labeling Law is going to solve all the ills of our country, and people who are convinced it’s only the first step toward completely banning anything that makes us happy to eat. The truth is that there is neither an evil plan against the freedom to eat alfajores, nor is the law only about front-of-package labeling. The public debate insists on staying there, but the black octagons on the packages are only the most visible expression of a complex solution to an even more complex problem. If we accept, in honor of the bare minimum of common sense, that the law does not seek to create a dystopia of clandestine alfajores, then… what does the law seek? Which products have to carry labels? What can we expect to happen from those labels? Why?

3/ The problem

On this we can agree: excessive consumption of sugar, fats and sodium is a public health problem, and it’s associated with the chronic noncommunicable diseases that most affect the global population: diabetes, high blood pressure, obesity, and many other vascular, cardiac, brain and kidney diseases. That’s how it is and there’s not much way around it. Particularly in Argentina, the three risk factors most associated with mortality are: hypertension, high fasting blood sugar and overweight or obesity. When it comes to overweight or obesity, Argentina has one of the highest figures in the region and it’s on the rise: it affects 4 in every 10 children and adolescents, and 7 in every 10 adults. Argentina is the country with the highest per capita consumption of sugary drinks, and we also have a very high consumption of ultra-processed foods: 185 kg per person per year. In fact, in the country, poor eating habits cause more deaths than drug use. Of course, diet is not the only factor at play: other important ones are tobacco use, sedentary lifestyle and alcohol abuse. And all of them should be addressed urgently. But while tobacco has carried warning labels for more than a decade, sedentary lifestyle and alcohol abuse are still not being tackled with large-scale public policies.

4/ Freedom, freedom, freedom

That’s the sacred cry. The problem is that freedom also comes in several flavors. Freedom for what? To be able to choose what we consume, of course. But to be able to choose truly freely, it is essential to understand what options we have. And, although it’s true that the ingredient table has always been available, it’s also true that in the second National Nutrition and Health Survey only 13% of the Argentine population understood the labels. And to top it off, the packaging often contained misleading information. For example, a spreadable cheese that used to be advertised as “light” and “42% less fat” now shows on its package that it actually has an excess of both saturated fat and total fat. Did the cheese change? No, what changed is how many liberties the manufacturer can take when communicating what’s in the product.

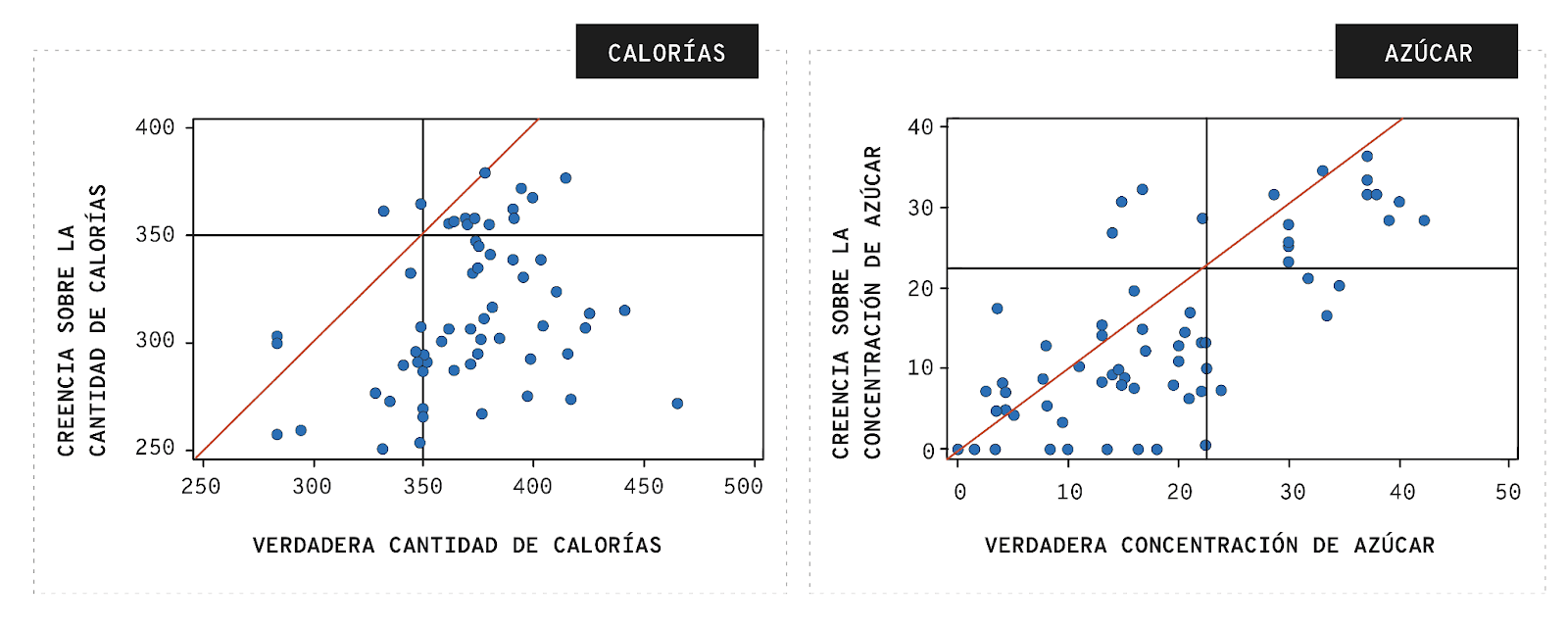

A recent study (which Nico Ajzenman covers in his newsletter Esto no es economía) shows that people tend to underestimate the calorie content of the products we buy, and sometimes also their sugar content.

In the study, they asked different people in Argentina what sugar content and how many calories they thought different breakfast cereals had. The graphs show the relationship between what people answered and the real values. If the dots lined up along the red lines, that would mean our perception of sugar content (or calories) is perfect. But that obviously doesn’t happen. In the case of calories, we see that almost all the dots are below the diagonal, meaning that we think cereals have fewer calories than they actually do. For sugar content, the situation is a little less serious, but most of the points are also below the diagonal.

The information we have is not enough to understand what’s in what we eat. But the problem is far from being a matter of national idiosyncrasy. In recent years, many countries have implemented some type of labeling with the same goal in mind.

5/ How many sides does an octagon have

Why were black octagons chosen? Do they serve any purpose? Around the world there are different labeling models to provide information about the nutritional quality of food. In some countries, for example, a traffic light system is used that sums up the information and categorizes foods with different colors. However, in a study that compared different warning systems, they found that the octagonal seal model is the one that conveys information most clearly and efficiently.

The Argentine law follows the guidelines of the Pan American Health Organization (PAHO), which call for the implementation of black octagonal seals with white letters to indicate an excess of 4 critical nutrients: sugars, total fats, saturated fats and sodium.

They also indicate excess calories in food and non-alcoholic drinks. In addition, black rectangles are used to identify when a product contains sweeteners or caffeine and therefore is not recommended for consumption in childhood.

The Argentine law establishes that each seal must occupy at least 5% of the surface of the main face of the package and cannot be fully or partially covered. Also, the seals must be placed on the main face of the package, or on both faces when the package doesn’t have one that is clearly main. In cases where the package is too small for the seal text to be legible (for example, candy), micro-seals are used, which indicate with a number which critical nutrients the product has in excess.

An important clarification is that the law states that these labels should be implemented only on processed or ultra-processed products, not on ingredients, so a bag of sugar will not have a seal that says “excess sugar”.

But how do you define what counts as an excess of sugar? How is it calculated?

PAHO has a “nutrient profile” that classifies foods according to their nutrients in order to prevent disease or promote health. In this way, it sets thresholds to determine which products need labeling, and this is calculated in proportion to the product’s total calories. These calculations are defined by the relative content of a critical nutrient according to World Health Organization recommendations. For example, excess sodium is defined based on the ratio of 1 mg of sodium per calorie. Not everyone has the same nutritional requirements or types of diet, but these values are guides for public health.

6/ Beyond the supermarket shelf

And here we get to the core of the matter: all this just to know that an alfajor has a lot of sugar? Well, no.

Although people generally refer to it as the “Front-of-Package Labeling Law”, its real name is the “Healthy Eating Promotion Law” (Law 27,642). And its goals are not only that we can know whether a product has an excess of a critical nutrient, but also to guarantee the right to health and adequate nutrition, as well as to prevent malnutrition in the population and reduce chronic noncommunicable diseases.

That is, the warning seals, while a fundamental part of the law, don’t exhaust it: there are three other main pillars that can’t be ignored if we want to discuss it.

The first is what happens in school environments: according to the law, foods and beverages that have at least one warning seal cannot be sold or promoted in educational institutions at the preschool, primary or secondary level. In addition, the Federal Education Council must promote the inclusion of minimum nutrition education content in schools. And yes, here there is a ban, and you could say we’re getting closer to the dystopia from the beginning, that future of clandestine alfajores. But we’re talking about school environments, places where it’s already forbidden, for example, to sell cigarettes or alcoholic beverages. So why not also ban the distribution of food products that have excess critical nutrients? There is research showing that interventions of this kind in schools can change eating habits and prevent the development of overweight and obesity.

The second pillar has to do with advertising, promotion and sponsorship. Foods and drinks that have at least one warning seal cannot be advertised to children and adolescents. In advertising aimed at adults, the seals must be clear and visible, and no childlike characters, cartoons, celebrities, mascots or other characters may be included. Because if someday you want to have a yogurt with excess sugar for breakfast, that’s perfectly fine, but what’s not fine is doing it believing that’s what Messi eats every day and that it will give you the energy you need to run ninety minutes without stopping.

Foods and non-alcoholic drinks that have at least one seal also cannot offer the chance to win prizes or gifts, physical or digital, cannot participate in raffles or cultural events, nor can they have logos or endorsements from scientific or medical societies on the package. They also cannot be given away for free or have their purchase promoted in order to make donations. And yes, I remember with nostalgia the tazos and little toys that came in bags of chips when I was a kid, but it’s also true that many times I asked to be bought chips just for the tazo. Fortunately, the law does not retroactively erase the happy memories of building a toy while eating chocolate; it only reduces the chances that some little kid will demand to be bought a combo with surprise hypertension included.

Finally, the law implies a commitment by the State to ensure that food assistance is of good quality. Today, with 40% of the population below the poverty line, the State is the main promoter of malnutrition at the national level. In Argentina, quality food is a privilege, and implementing the law should help turn it into a right. Both in price-control programs and in food purchases for schools and community kitchens, ultra-processed products are currently everywhere. With the law in place, the State must prioritize purchasing products that do not have seals.

In short, the real goal of the law is for the eating habits of the Argentine population to change in order to reduce the risk of chronic noncommunicable diseases. A key step for these changes to happen is opening up conversations about what we eat and what we don’t, conversations that hadn’t been taking place for a long time and that now have appeared. This is perhaps the law’s first victory. We’ll only know the results in terms of changes in habits (good, bad or neutral) in a few years or decades. However, we can ask ourselves what we expect from the future based on what happened in other countries.

7/ What comes next

Chile was the first country to implement this type of regulation at the national level. The authors of the same study in which they concluded that people tend to underestimate how many calories a product has also looked at changes in consumption in Chile after the law was implemented. In particular, what they found is that consumption of products with warning seals dropped relative to products that don’t have seals, meaning the law did have an impact on what people choose to buy.

But the impact was not the same for all products; it was more marked in products whose calorie content we, as consumers, tend to underestimate. What does that mean? That after the law, people kept eating alfajores when they felt like eating alfajores, regardless of the warning seals, but when choosing what to buy to take to the doctor’s waiting room, they often stopped grabbing a pack of water crackers thinking they were healthy.

The authors also found that, once the law was implemented, many products were reformulated to have just enough critical nutrients to fall below the threshold at which warning seals apply. And while some people interpret this as “where there’s a law, there’s a loophole”, the reality is that this is a positive effect. After all, it’s desirable for formulations to be changed so that the products we buy are healthier. In Argentina, for example, by April 2023 there were already products whose recipes had been changed so they would have no warning seals. And not only did they change the recipes, in the ads they highlight the fact that they are seal-free. Perhaps in a few years PAHO’s standards will change and seals will apply at even lower thresholds than today, and again, it would be completely desirable for producers to modify their recipes once more.

Lastly, in Chile the prices of products without labels went up more than those of products with seals. It’s hard to predict the economic effect that implementation of the law will have in our country, but eating healthy has always been more expensive and this precedent reinforces the need for the State to guarantee access to real food for everyone. Because having the information is necessary, but not sufficient, if at the time of buying you don’t have enough money to choose the healthy option.

8/ Clandestine alfajor

So? What future awaits us now that we decided to ruin the supermarket shelves with slightly more truthful information?

Most likely, if March 5th, 2030 finds me sleepless, it’ll be because of an unprecedented heat wave and not because I’m breaking the law to go buy an alfajor.

It’s also likely that in seven years I’ll still be eating almost the same number of alfajores I eat now. But maybe my nephew at summer camp won’t be given chocolate milk that has more sugar than cocoa, or my friend’s daughter at kindergarten won’t be made to have spoonfuls of sodium for breakfast every day. Maybe it sounds strange to put it this way, because we are creatures of habit and if we’re used to anything it’s to pessimism, but what can I say: it’s a better world.

This article is the result of ongoing conversations with the people behind Consciente Colectivo, a socio-environmental activism organization that has been working on front-of-package labeling for a long time.