Access

You may be a very poor person or a very rich person, healthy or sick, altruistic, misanthropic, naive, malicious, entrepreneurial, a poet with a broken heart, a tree hugger, a gearhead, a dull office worker, a colorful office worker, a scientist, an intellectual, a lawyer, an accountant, a printer, a railway worker, a soccer player, a kiosk vendor, a dog walker, a financier, a gastronomy worker, a person who listens to the radio so as not to feel alone, a smoker, a bodybuilder, a precarious worker, a person who appears on television or a person who works so that others appear on television, someone who devotes themself to music or to sociology, to theater, to transport, to teaching or to metalworking. We have no way of knowing. But it’s almost certain that, if you are reading this, you live in a city.

Your city may have large and beautiful pedestrian bridges that cross rivers full of fish, or it may have narrow, dusty streets combined with wide avenues packed with cars that make them impossible to cross. The edge of your city may border the sea or an informal settlement that is also part of your city, even if the municipality does not recognize it. Perhaps you live in the cultural beacon of the region and the big bands always stop at the stadium near your house, or perhaps your city is the cradle of still-unknown artists who will make it famous in the future, because no one yet knows the name of your city. Everyone has at some point seen, in photos, the famous monument built by that now deceased architect and, even so, it is possible that your city only recently became known when the player who was born there became world champion, and now he too has a monument at the entrance to the highway. Maybe your city is not even your city, because you moved to start a degree that is only offered at a certain university located in a specific part of the country, far from your family but closer to fulfilling your dream. Maybe you lived your whole life in the same apartment, but in your neighborhood there are now flavors from countries you had never tasted and your neighbors practice religions that seem inexplicable to you. Let’s admit that your city has serious problems with garbage collection. You would like to move, but at least here you already know the names of the streets and you can get around with your eyes closed. You would like to be in touch with nature, like in the photos of those exotic cities where the buildings look like giant metal fruits growing among the vegetation. Still, the European style speaks to you. And if you can choose where to lose yourself, you take a book and head to where the streets narrow and start to have nooks and crannies, little squares hidden around an unlikely corner, among moldings and antiques. You like new faces; you enjoy guessing what country those tourists might be from. And the cultural circuit drives you wild. Or perhaps your city is a barren expanse of low houses, where everyone has huge pickup trucks, things are far away for so few people and nature is a desert, as it has always been. And that’s fine. There is pride in that wind you grew up with, even if it is torture. You heard that in the city next door people are kinder, that the traffic lights work better, that the mayor fills the potholes. It makes you a little jealous, of course. You’ve traveled. You know there are prettier cities and yours can’t seem to shake the vices you’ve known since you stopped playing on the sidewalk. Now they’ve put a mall half a block away and there is a constant coming and going of people, brands, cars. You go to the mall too; it’s close. It has a cinema. But you can’t stop fantasizing about going far, far away from everyone, to live in peace and silence. It is unlikely that you will do it. The most likely thing is that, besides living in a city, you are an urban creature. And not because you are fascinated by road rage or rush-hour commutes. What you like, what you cannot let go of, what you inevitably need – even in moderate doses, even from time to time – is other people.

Old town

More than 80% of the people who live in South America live in cities. In some countries – such as Argentina – that number climbs to 90%. Which, put another way, means that 9 out of every 10 people – by choice or trapped by circumstances – live close to other people. More scattered or more crowded, in peace or with multiple conflicts, in the center or on the outskirts, but with others. Grouped together. There isn’t even a clear universal parameter for defining what a city is. While China requires a minimum of 100,000 inhabitants, Denmark sets the bar at 200. In any case, we are always talking about a system of coexistence based on an infrastructure, so inescapable that it is frightening, so beautiful that it makes you fall in love.

What do we know about that system, that infrastructure?

Urbanism as a university degree has existed for a few decades, but the practice of designing cities goes back several thousand years. As an emergent phenomenon, it has existed since we put one little house next to another. From that time until today, we have designed cities with all kinds of purposes and mispurposes. We built walled cities to protect ourselves from the enemy, poorly ventilated cities where plagues decimated us, monumental cities for gods that do not exist or for the dead who cannot live in them. We raised cities perfectly designed in advance, harmonious and symmetrical, and we also piled up stone after stone without a defined plan, guided by necessity, immediacy and intuition. For better or for worse, we have never stopped designing, building and inhabiting cities.

But no design is neutral. All design is political, and in the case of urban design this is true in a very direct sense, because altering or creating something new in a city changes people’s lives. The impact of these acts of design is highly variable and depends, among other things, on who the people carrying them out are, with what class, ethnic, gender biases, and who the people are who suffer or enjoy them.

However, there are some universal truths: for example, that cities change. They are a verb, not a noun. A constant becoming. In fact, we call places where there are no people, no life and no movement “ruins.” Every day when you get up and leave your house – whether by car, by train, on foot, to study, to buy something, to work – you are making your city. Making it in a way that is more relevant to the overall ecosystem than if you built a new building.

There are other truths that may be a bit more uncomfortable: there is a very high chance that the city where you live was designed for automobiles, not for you, and this does not even depend on whether you drive a car. There are also high chances that your city is not prepared to deal with climate change and that a heat map reveals areas that are increasingly uninhabitable. It is certain that many of the other people who live in your city do not share your political opinions, and moreover, that they do not share your ideas of what the city should be like. And if you have sons, daughters, are an older person or a person with a disability, or if you are living in poverty – in other words, if you are the weakest user – your options for enjoying the city have just been drastically reduced.

But calm down, not all is lost.

Monument

There is a particular type of citizen: the one who, in addition to inhabiting the city, is in charge of managing it. This is at once a job like any other and an exceptional honor. Since cities are subnational entities, there is a whole universe of laws that mayors, local representatives, legislators and other officials cannot bend or bypass. But the remaining margin is immense. As immense as the responsibility. If by chance you are reading this and remember that your monthly income is justified by a certain power that the people placed in your hands, there are also some things you need to know.

Every city is the result of a tension between the individual, the civic and the living. Elements that can be balanced and, better still, can be set in motion with political will. The bad news is that things are not as simple as “listening to the neighbors.” First of all, the neighbors are not always right. Some are right and others are not. Or worse still, they can all be right and want different things. For example, reducing parking spaces to recover pedestrian life is almost always a good idea, except if you ask the handful of drivers who use those spaces. Cutting down a tree is seldom justified, but if the lot is going to be used for social housing that helps reduce rental prices in the area, properly increase density and improve neighborhood safety, it may be worth considering. In general, these kinds of disputes require a great deal of dialogue, agreements, compensation systems, analysis by professionals from different disciplines and a not insignificant dose of will and good reputation. Many choose to let the clock run until it becomes someone else’s responsibility. Luckily, you’re not one of them.

The good news is that there is a minimal viable urbanism that is also politically profitable. Things that do not involve too much budget and never get bad press: lighting, flower beds, proper lane separations, trees, plazas and (non-hostile) street furniture usually work as a guarantee of reelection to office. There are plenty of examples around the world. Sometimes the difference between good and evil comes down to drawing a line, usually with yellow paint.

And then there are the big things, reserved for those who seek bronze. We are talking about trains, subways, housing, schools, mitigating climate change, turning highways into green corridors and uncovering piped streams. The true urban epic. Yes, it is harder. Everything has to be done under a storm cloud, while above, in the winds of national politics, other kinds of forces operate, much more titanic, dark and unpredictable. But you can start small. Making better cities, managing and distributing access to public space, taking care of the inhabitants, developing infrastructure and boosting quality of life by every possible means is, at the end of the day, your responsibility. Let’s put it this way: if you want them to erect a monument to you in the square, you first have to build the square.

People at work

Fortunately, there are also many things that can be done that do not require the – sometimes heroic, sometimes half-baked – decision of a mayor. A type of urban design that is, first and foremost, optimistic. It consists of smaller or larger interventions that emerge from the bottom up and can transform cities one little piece at a time, until they become what they were always meant to be: the best place to live.

The inhabitants of small cities on the outskirts of Delhi and Mumbai (India) took the initiative to plant 111 trees for every girl born. Tokyo, one of the densest cities in the world, has a practice called taiken-nouen, which consists of using building rooftops to create collective gardens, where workshops on urban horticulture are also given. Valencia does the same with vacant, unused lots in the city center. In Barcelona, groups of parents who took and accompanied their children to school by bicycle organized themselves into corridors to do it together and provide safer conditions.

Do these examples smell too much like the First World? If you think so, it is only fair that you know that the bicibus is a practice that has spread to other cities around the planet and today some schools in Argentina replicate the experience at the initiative of their parent associations and teachers. In the Almagro neighborhood, a group of neighbors protected a vacant lot where native plants grow, turning it into a nature reserve and inner-block green lung that helps lower temperatures, breaks up the concrete stain and improves everyone’s quality of life. There is also a Telegram group where neighbors share worms, compost, wood and dry material to reduce the amount of waste they generate and then have fresh soil for the plants in their homes. In Rosario they built community gardens. In Bogotá and Medellín they close streets on weekends to make them pedestrian. In Lima they organized to restore run-down neighborhoods, Santiago de Chile has street libraries and in Montevideo they formed a full cultural center. Neighbors in certain favelas of Rio de Janeiro organized a new and better layout for their streets. In Villa Domínico, neighbors planted trees along the highway and, once they grew, the municipality came to plant the rest and tidy up the line. In Córdoba they recovered a historic brewery – an emblem of the neighborhood – and turned it into a museum. In Villa Martelli, they closed off a few blocks to create a “superblock” where children could play again. In Empalme Norte, Rosario, they improved access roads that were impassable on rainy days, as well as infrastructure, lighting and the planting of native species, all done by work crews from the same neighborhood who later organized a worker cooperative. In different parts of Greater Buenos Aires, good Samaritans have been seen improving their neighbors’ lives simply by putting an inflatable pool out on the sidewalk on a scorching summer day. And a van from a repair club drives through the streets of Buenos Aires offering services and workshops, before returning to its headquarters in Villa Crespo.

The real list is endless. None of these ideas die within the walls of the city where they were born. They are effective tactics because they are generous, and generous because they are replicable. And they do not require much to carry out: a flower bed, a park without fences, a painted line, a WhatsApp group, a few folding chairs in the street, a set of cones carefully arranged while the use of that space takes hold and there is no choice but to build better and more permanent infrastructure.

It is dynamic, it is exciting. It is pure urbanophilia.

Land registry

This book is about these things. About cities, understood as something more than skyscrapers and avenues. Here is an ode to the streets, but not to cars. A set of ideas for rethinking the places where we live and an incitement to transform them. We cannot provide precise instructions because every city, every neighborhood, every corner may require different solutions. But we can offer some keys. And the reasons to put them into practice.

In this book you will find mentioned – for different reasons, in this order of appearance but often repeated – the cities of Barcelona, Bariloche, San Juan, Santiago de Chile, Lima, Buenos Aires, Montevideo, Amsterdam, Brasília, Medellín, Cusco, Ocongate, Tinke, Bamenda, Greater Buenos Aires, Santa Fe, Rosario, Córdoba, Mexico City, Guatemala City, Seoul, Montreuil, Paris, Prague, London, New York, Bahía Blanca, São Paulo, Vienna, Berlin, La Plata, Copenhagen, Los Angeles and Venado Tuerto.

You will also find twelve keys needed to rethink your city, make it your own and transform it. These sections deal with: 1) the five basic elements of urban design, 2) places vs. non-places, 3) hostile architecture, 4) the importance of designing cities for people, 5) the arrogance of space, 6) desire lines, 7) nature, 8) superblocks, 9) density, 10) land value, 11) the digital disruption of cities and 12) tactical urbanism.

The four chapters ahead of you were written by Federico Poore, Laura Ziliani, Felipe González and María Migliore. They talk about the block, the street, the neighborhood and the city, respectively, as if it were a great zoom out, a shot that opens up, a camera that moves away and loses definition but gains complexity.

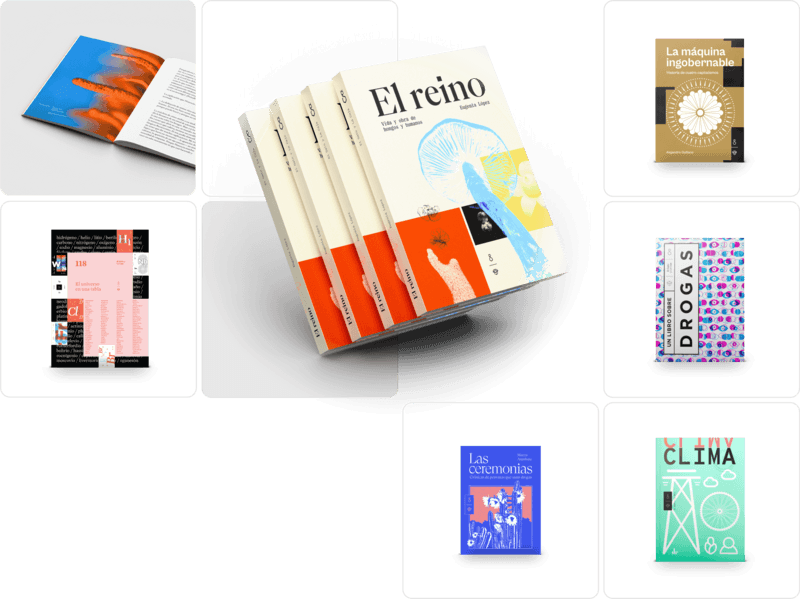

The reading experience of this book moves through texts and images. Its minimum units are the word, the graphic and the photo, and the editorial design that brings them together aims to illustrate and inform in an orderly way. From the text box to the spine you will see on your bookshelf, this graphic identity system is an exercise in approaching the spaces in which we live – but also in appropriating them – in order to seek out other possible and desirable forms for them.

If you have the physical version of Urbanofilia, then you have a book printed in four colors, on 152 pages of 80 g Avena paper and in the size we consider ideal to hold in your hands.

However, this book is also like your city: not even the most detailed land registry can replace the experience of going in and walking through it. Living it.

Preferably, slowly.

And sharing it.