Cassandra is the protagonist of one of the bitterest stories in Greek mythology. Apollo, god of the Sun, knowledge and truth—among many other things—fell in love with her and gave her the gift of prophecy, seeking with that divine gift to win her affection. Cassandra did not return Apollo’s love, and he, now a god scorned by a mortal, unable to revoke the power with which he had endowed her, decided to add a curse: Cassandra would be able to see the future with certainty, but no one would believe her.

The gift and the curse worked in equal parts. Cassandra’s warnings became part of the soundscape of the fall of Troy. Unintelligible noise for both kings and slaves, and folklore of tragedy.

Almost 200 years ago, the scientific community had the first indication linking the emission of Greenhouse Gases to the rise in our planet’s temperature. At first slowly, then increasingly quickly, we built knowledge and consensus that led researchers to better and better understand these phenomena and to project their long-term consequences. For more than 50 years, certainty about the relationship between Greenhouse Gas emissions and climate change has been total. But when this idea escapes the confines of the specialized community and seeks to impact the actions of individuals, communities, companies and States, it encounters the same limits as Cassandra’s prophecies. The voice is heard, clear and defined like a stone falling into water. But it sinks without making ripples.

If we look back at past predictive models, we can see their worrying success in predicting a present that used to be the future. In that future—in this present—we live every day more than 1 °C above the pre-industrial average, with extreme weather events becoming ever more frequent and with concrete and tangible repercussions, merely the beginning of the path that leads to a bleak future. Fortunately, in this present we are also building ever better predictive models, which tell us stories of possible futures and show us another path, the one that leads to what may be.

The good thing about the future is that it always exists in a state of probability and that it also depends on our actions. There are futures in which we change our relationship with the environment, or even our perception of that relationship. Futures in which we design the systems that sustain our species so that they function from, between, in relation to and as part of nature. Futures in which we understand ourselves as a single interconnected living system, not divisible into subspaces.

To get there, the keyword is design, as our tool for transforming the world. Because without science it cannot be done, but with science it is not enough. Predicting the future is a very different task from bending it, and to do something, we have to do it. This book is an attempt to contribute to the urgent ecosocial transition we need to guarantee the survival and flourishing of our species on this planet: the greatest design challenge of all time.

Fortunately, we are a species of natural designers, capable of using our critical sense to identify a problem, creatively build a solution and put it into practice. Diffuse forms of design that everyone experiences. A species that designs is one capable of materializing concrete solutions that express intentions about the world. But not only to build it, also to narrate it. Because the other great way of designing is to construct meaning. Framing, cropping, presenting, visualizing ideas, stories, memes, in such a way that they stimulate sensitivities and change the way someone understands the world.

In addition to being a natural ability, design has been refined into series of specific practices: the multiplicity of disciplines of the feasible that some people also choose as a professional occupation to build value and meaning in more and more environments. We are talking about graphic design, industrial design, architecture, but also engineering, business, education, medicine and even—and above all—public policy design. From these practices and professions we will be able to take tools that serve to imagine, design and effectively build the future we want to move toward, breaking inertia and avoiding Cassandra’s fate.

But the transition is not just any challenge. It is a complex problem, defined as such not as a synonym of difficult, but on the basis of specific properties: complex problems are problems in which we deal with massive and incomplete information, they usually involve highly interconnected systems and actors in tension. They do not have a single solution, each attempt at resolution carries risks and there is not even a well-defined end point.

But far from being exceptional, these challenges are ubiquitous and we navigate them daily. We accumulate experience with each one. From that experience, we learned, among other things, that they respond better to an interdisciplinary approach, capable of understanding, framing and addressing them from multiple perspectives; and that this interdisciplinary approach implies a language challenge that is easier to solve by starting from the end: building visions of desirable futures in which the problem has been solved, a shared common point we can cling to, despite being different people with different perspectives or, even better, precisely because we are.

Desirability is one of the three fundamental lenses through which the perspective and methodology of Human Centered Design approaches problem-solving and the design of innovative products and services. Along with desirability, this methodology also integrates the possibilities of technology (feasibility) and the requirements for that product or service to succeed in economic terms (its viability). This way of approaching innovation has been very successful. It has become one of the most popular and widespread approaches to design thinking today, and one that, we believe, we can disassemble and reassemble to fit the needs of this challenge.

The desirability we propose does not operate in individual terms, but collective ones. We reclaim the question “what is a desirable future?”, but establish a necessarily shared framework. Any individual desire will be secondary to our agreements as a species. In the same way, the commercial success of the solution we pursue will no longer be what defines the viability of a project; instead we face the hard limits of thermodynamics. If a solution is not compatible with the biophysical limits of our planet, it will not be sustainable. Finally, any solution we aspire to will have to be feasible to execute by the team that undertakes it: team humanity.

The greatest agreement we have reached as a species about what a desirable future is, is expressed in the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) of the United Nations. These 17 goals (also expressed in terms of concrete targets and indicators) capture the priorities that 194 countries have agreed upon as a horizon. Among them are “end poverty in all its forms everywhere”, “end hunger, achieve food security and improved nutrition and promote sustainable agriculture”, “ensure access to affordable, reliable, sustainable and modern energy for all”, “take urgent action to combat climate change and its impacts” and “protect, restore and promote sustainable use of terrestrial ecosystems, sustainably manage forests, combat desertification, and halt and reverse land degradation and halt biodiversity loss”.

At the same time that we have managed, as team humanity, to agree on goals, we have made progress in defining the hard limits of sustainability. Those imposed by the major biophysical systems that keep our planet in the kind, balanced state we have known for the last 12,000 years and that today are under strain from our actions. These thresholds that we must not cross have been conceptualized, defined and ordered as planetary boundaries, and they are: the climate crisis, ocean acidification, depletion of the ozone layer, the balance of the nitrogen and phosphorus cycles, water use, deforestation and other land use changes, biodiversity loss, atmospheric particulate pollution and chemical pollution.

Crossing any of these boundaries means increasing the risk of a breakdown in equilibrium with potential systemic effects on all the other limits of the Earth system, with consequences at the same time impossible to predict precisely, but irrelevant once we understand that our survival depends on remaining within the known ranges of all these systems. Tolstoy opens Anna Karenina with the idea that “All happy families are alike; each unhappy family is unhappy in its own way.” All Earth systems in which we prosper resemble one another, while systemic imbalances each express their own way of increasing the suffering of every sentient species on our planet.

We therefore understand what is desirable and what is sustainable in our enormous design challenge and, moreover, we have begun to understand the relationship between the Sustainable Development Goals and the planetary boundaries. Researchers have modeled the futures that await us in different situations: 1) if we continue with our Business As Usual, that is, developing models of unlimited growth guided solely by the measurement of Gross Products; 2) if we do so by improving our current systems beyond any prior improvement target that we have ever experienced in history; or 3) if we pursue a profound ecosocial transformation. Only this last model, the transformative one, leads us to a 2050 in which we not only return to operating within almost all the planetary boundaries, but at the same time meet the SDGs. All the others involve some kind of suffering associated with climate change, more or less deep, more or less widespread, that we could have mitigated.

This possible and desirable future we can choose to move toward necessarily implies questioning infinite growth and its ambition. It implies developing sustainable systems that are durable in the medium term, the active redistribution of wealth, permanent investment in education with an emphasis on gender equality, the large-scale redesign and implementation of sustainable energies and the shift of our food matrix to a sustainable one in which a plant-based diet predominates.

We know, then, what we have to do to navigate the present toward a future that is not only possible, but sustainable and desirable. Now we must focus on the last element of those design lenses: feasibility.

We are going to turn the unproductive mandate of “we must” into a design question: how might we? How might we change the energy matrix in a Global South country embedded in a particular geopolitical context? How do we get half the inhabitants of a medium-sized city to travel by bicycle? How do we get vegetable producers to use half the fertilizers they use today? How do we change the dietary choices of a person who is forced to eat away from home every day? How do we convince the person next to us that this is urgent and important?

That is where we understand design in its broadest form: “Design is a culture and a practice about how things ought to be in order to attain desired functions and meanings,” says Ezio Mancini in Design, When Everybody Designs. This vision encompasses both the construction of practical solutions and that of meaning. This project represents an attempt to contribute to both. Imagining it, designing it, developing it and sharing it required bringing together an interdisciplinary team, nourishing ourselves from that diversity, accepting tensions and choosing design as our common language.

In part 1 we organize the whys. Reasons, diagnoses and predictions. The story that leads us to understand why we need a profound change. We contextualize the climate crisis and the possible futures that await us and that we can model through science depending on our actions.

But looking at the future only as a projection of the past is to surrender to Cassandra’s curse. That is why, in part 2, we put forward concrete ideas about energy, mobility and food, the systems with the greatest impact on Greenhouse Gas emissions and, therefore, on the planetary boundary of climate. How to transform them. What we have to do.

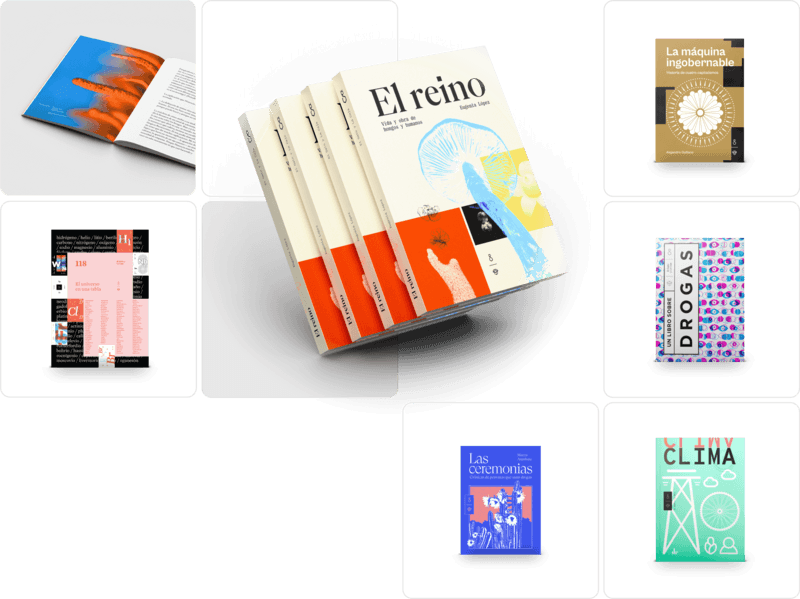

Understanding the goal, while a gigantic step forward, is not a solution. The solutions we need are multiple, massive, and depend on each scale, territory, culture, context and history in which they seek to be put into practice. Knowing this, for part 3 we invited three interdisciplinary teams of doers, not to tell us complete solutions, but different perspectives on possible solutions that navigate different complexities and serve as a small but real sample of the existence of people, projects and organizations actively involved in navigating the transition. These chapters not only bring into play stories and proposals for technical solutions, but also the disputes and constructions of meaning that we need in order to achieve a just sustainable transition.

This project—the book as a whole, but also what we do beyond it—joins the efforts of every person who has ever dreamed of a sustainable future in which our species thrives in balance with the natural systems of which we are a part. Put in perspective, it is a small effort, yes, but a sincere one. This is our space race, the human feat that will mark several generations. This time, the adversary is collapse, and the only way to achieve a transition toward a desirable future is to spread hope in its most active form. Breaking Cassandra’s curse means accepting, imagining and solving the greatest design challenge of all time.

August 2022